Mathieu Canet Interviewed by Lucia Bell-Epstein and Siân Lathrop

Continued from: ~Oeufs Mimosa – Food Journals from a Month in Paris

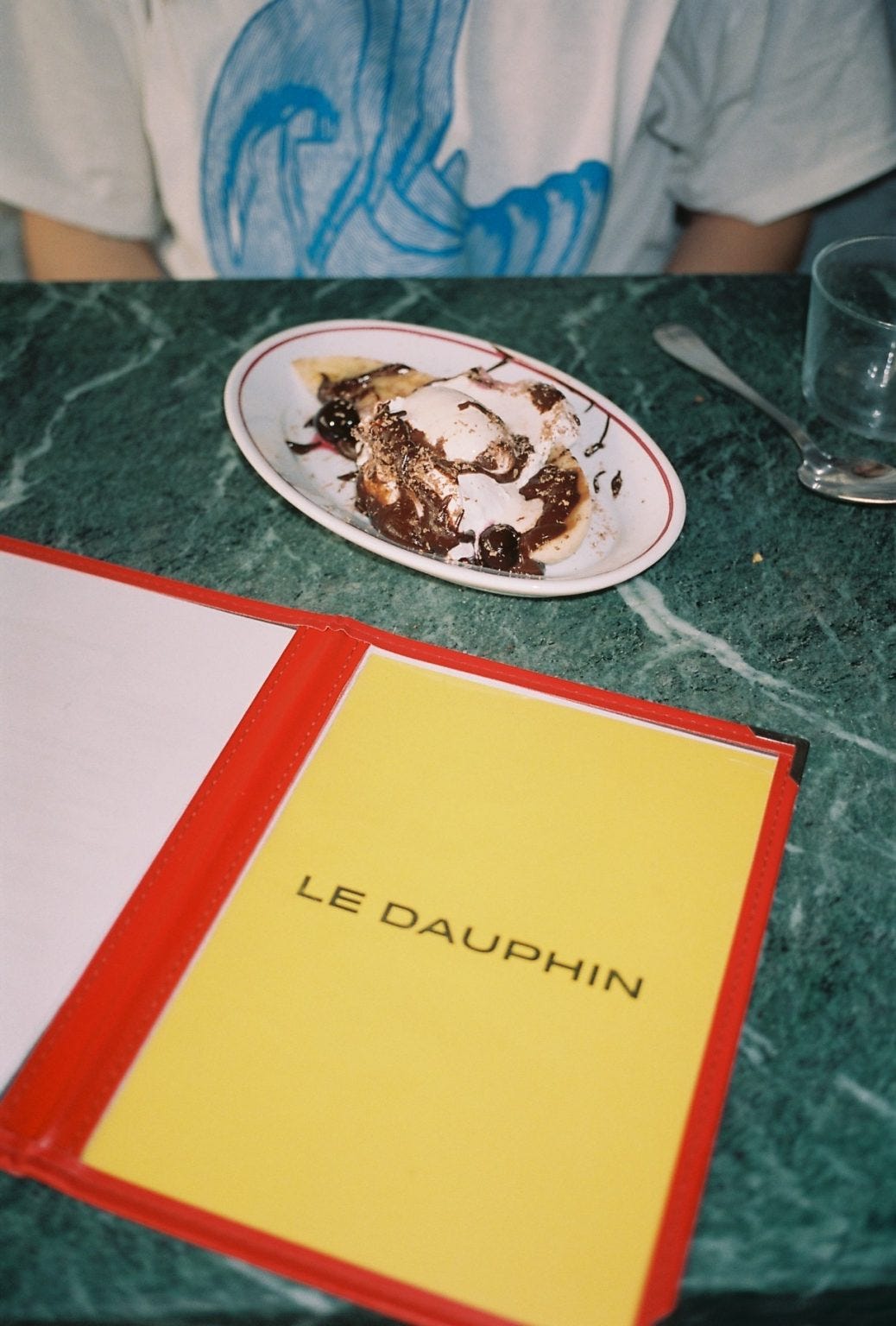

“...Ready to eat, we meet Simonez for lunch on a beautiful Saturday afternoon. All three of us arrive at Le Dauphin, the sister restaurant of the renowned Chateaubriand, around 1:15 PM.

The two restaurants sit beside each other on Ave Parmentier, and are credited with putting the 11th arrondissement on the map. While the Chateaubriand is known for its experimental plates, Le Dauphin does beautifully executed classic French food and wine.

The atmosphere in Le Dauphin is unmatched. The restaurant was designed by Rem Koolhaus, and the space makes a visit to Le Dauphin worth it even before you’ve started eating. The menu is warm and familiar, a contrast to the coldness of the marble interior.

Simonez is friends with Chef Mathieu Canet and has set us up to interview him. We order Oeufs Mimosa to start, and Chef Mathieu sends out grilled fish for us. The menu is deceptively simple, everything is in season. We have a salad of cilantro, a plate of grilled leeks with vinaigrette, and a ricotta and spinach tart. It tastes like spring. For dessert, a twist on the American classic, a banana sundae.

We are served food on plates that, when polished off, reveal a tiny red dolphin. As we eat, I can’t help but laugh. The restaurant seems to wink at itself. We are sitting in a marble box, listening to music playing out of black modernist speakers, and yet here we are eating the most classic French dish you can think of: Oeufs Mimosa. It is fantastic.

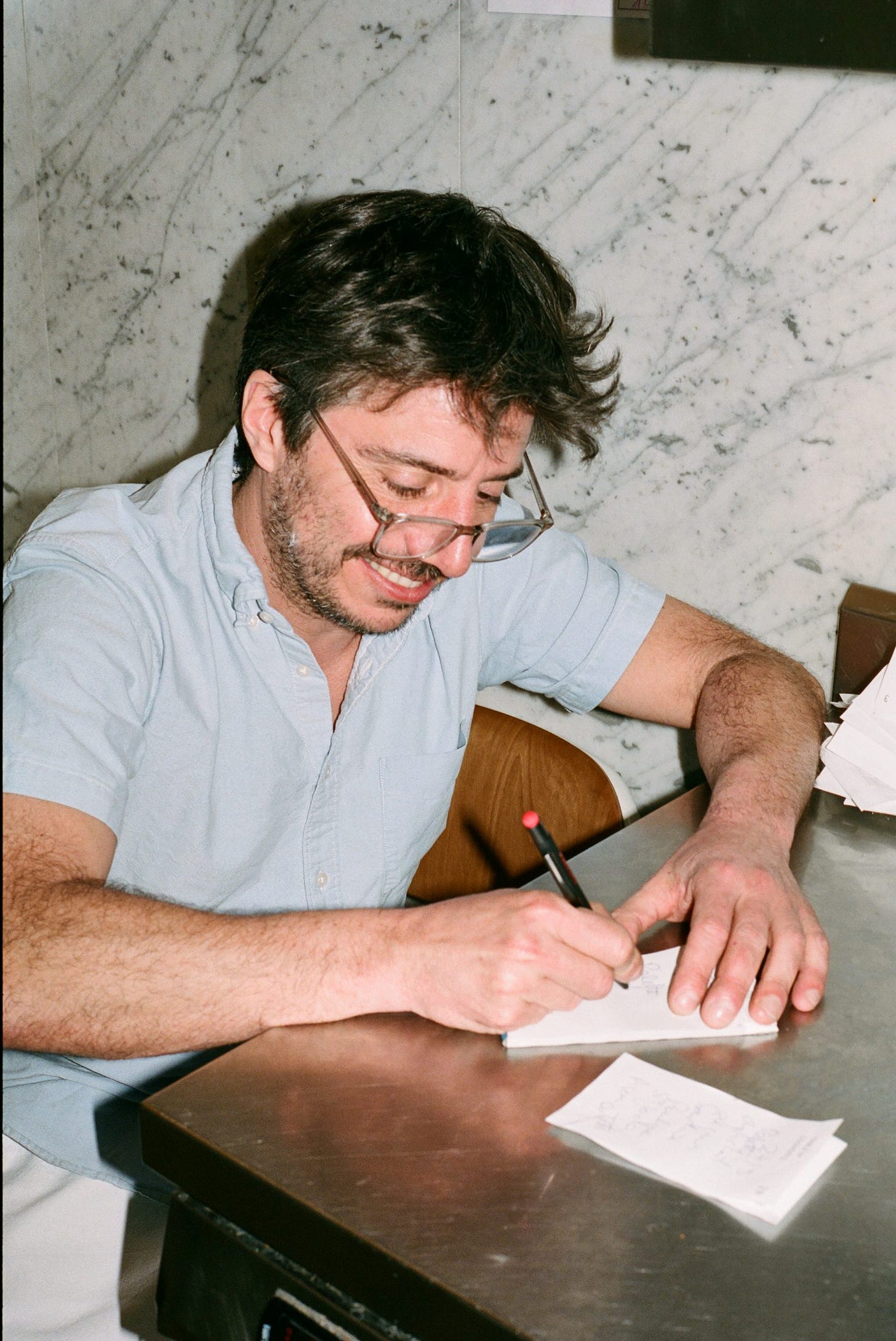

The restaurant closes so the kitchen can prepare for the dinner service but we stick around, waiting to speak to the Chef. Suddenly he’s sitting at our table in a big black puffer jacket. He makes everyone espressos and smokes a cigarette. “I am trying to make food that is really legible, very understandable and palatable to everybody.” Chef Mathieu’s philosophy is simple: Good food should be accessible. He emphasizes working with good suppliers and food that is in season: “This week is the start of the asparagus season. So this week we will serve asparagus.”

He moves around the marble box, reaching over the counter for another espresso. “The space is brutal, but that brutality is cut by comforting food. There’s no bullshit.” He’s an intimidating figure, tall and bearded, but he moves with grace. His favorite musician is Arthur Russell, the cult figure & disco cellist who died of AIDS in 1992. Russell favored the simple and straightforward – a minimalist with a cello. I am probably reading too much into this, Chef Mathieu isn’t reflecting on why he likes Arthur Russell. He just does.

We sat with him for an hour and spoke in mostly English mixed with a bit of French. Chef Mathieu describes how important it is for him to remove his ego from the food he cooks: “I want to turn away from myself as an individual and learn from the people who came before me. Credit them. The stuff I cook has a lot of references to French classics. If you get the reference that’s cool. But you don’t get the reference from the 200 year old recipe, you can just enjoy your meal. No judgment.” The food and space support Mathieu’s intentions. There is a strong sense of community between the people that work at Le Dauphin, both between front and back of house. It makes sense why there is not much turnaround, most people in the kitchen have worked there for 3 to 5 years…

Lucia Bell-Epstein: How is the food inspired by the architecture of this restaurant?

Mathieu Canet: I am trying to make really, really simple food to break with the architecture of the space. And with the kind of customer who comes into a high end restaurant like this. I am trying to make food that is really legible, very understandable and palatable to everybody. Without judgment. It’s pretty hard to talk about what you do. But I hope you get that sense of that when you eat here.

LBE: How long have you been cooking here?

MC: I’ve been here for 7 years. I came here to work for Inaki Aizpitarte. He’s the guy who owns the two sister restaurants, Le Dauphin and Le Chateaubriand.

I’m from Bordeaux, in the South-West of France. I had a very typical start in cooking. Worked in a Michelin restaurant in Bordeaux after cooking school. It’s called Saint James, by a really well respected architect: Jean Nouvel. It’s funny because he is a big name in architecture, and so is Rem Koolhaus, who designed Le Dauphin.

Siân Lathrop: Do you care about design?

MC: Well, Apparently I do. Yes.

LBE: The way you were taught, did you have to unlearn and break certain rules ?

MC: No, I don't think about cooking that way. I don’t want to break anything.

SL: Really? Nothing? You don’t want to change anything?

MC: No. That way I can feel the connection with the history of what I am cooking and the people I am cooking it for. Keep it simple. I don’t want to put pressure on customers in my restaurant, like, “you need to understand this way or this way”. It’s why I like to give people simple food, you don’t need to explain anything.

SL: No philosophy?

MC: Exactly yeah. I just want people to feel the kindness behind it. I just want everyone to be comfortable.

LBE: How does living and working in Paris inform the cooking that you do ? Has it changed since you came from Bordeaux?

MC: It changed from Bordeaux for sure. But honestly? I don’t really think too much about what I do. No reflection. I just work with good suppliers. Like this week is the start of the asparagus season. So this week we will serve asparagus.

LBE: What are 3 ingredients that you’re excited about?

MC: The asparagus, both the green ones and the white ones. It’s spring and there are vegetables coming in little by little, with the sun. But I like all the seasons, “c’est cool”.

That is why I say there’s no reflection behind what I give to people. We prepare simple food. Food that is in season. We don’t have 2000 people working in the kitchen.

SL: How did Covid affect your work?

MC: It was a good period for me. I didn’t cook during Covid. It was the first time in my life that I had time for myself. I have been working since I was 14. It was good to have time. I read.

SL: What did you read?

MC: I read Paul Marchand. He was a reporter. The book that stayed with me was Sympathy for the Devil, in which Marchand covered the conflict in Bosnia. Marchand was very sure of himself and took a lot of risks. He was different from other war journalists: he wasn’t staying in hotels, he was on the ground in the conflict.

His main point was that nobody can understand war, it’s so horrible. Although he took risks, he didn’t blame other journalists for not doing the same as him. Everyone has their own truth and he didn’t think he was better than others. This relates to what I was saying earlier about not putting pressure on people, you know? Nobody has the truth. You just have to let people live. That’s the connection with my work. I think that’s what really characterizes what I do. Not putting pressure on people, doing something simple, which is understandable to everyone.

I watched a lot of films as well.

SL: Like what?

MC: Cannibal Holocaust.

LBE: Do you feel like art informs anything that you do here?

MC: No. Everyone can make art. Even if you work in a bank you can make art. What informs my work most is simple: be kind to people. Try to put a smile on people’s faces. It is true, there are Chefs who are artists. But it’s way too easy to say “ah because you’re a chef you must be some kind of artist.”

It is pretty rare that there is real thinking behind a dish, real knowledge. 50% of it is bullshit, there’s nothing behind it. People call themselves artists but they can’t talk about what is behind the work they do, the meaning of what they are cooking. It is empty. No feeling. It’s sad.

I mean, as a Chef it is easy to emphasize yourself as an individual, to make everything about yourself. People like this have way too much vanity, way too much ego. I want to turn away from myself as an individual and learn from the people who came before me. Credit them. The stuff I cook has a lot of references to French classics. If you get the reference that’s cool. But you don’t get the reference from the 200 year old recipe, you can just enjoy your meal. No judgment. I hate the idea of the big famous French Chef coming to the table and taking credit for the meal. To me that’s horrible.

LBE: I really feel a sense of community in this space.

MC: Yeah that’s cool. I’m happy you feel that because it’s real. There is one guy in the kitchen, he was a waiter at the Chateaubriand and wanted to be a cook so he came to work for me. There’s another guy who’s been here for 3 years. The sous-chef under me has worked here for 3 years as well. The guy who does the dishes has been here 5 years. There’s this other guy who’s worked here for 4 years. So not there is not that much turnaround. People stay here.

LBE: In New York places usually have a fast turnaround.

MC: Yeah here too. That’s why this place is special. And I’m glad you said that because it’s true. Maybe it’s a bit too much to call us a family but yeah, it feels like a family. You want another coffee? I’m gonna make myself one.