Panoptic Party People

Written by Evan Moore

In March of 2018, I was sitting in Newark International Airport waiting for a flight that had been delayed for seven hours. Losing hope, I tweeted “Ending it all,” the intended punchline being the location tag of the airport. I sent the tweet and did not think about it again until I boarded the flight. Later, I got a text message from my mother saying that the Port Authority of New York had just called her. In post 9/11 America, surveillance measures have greatly increased in airports, something I had not questioned until that moment. They chose to call my mother because they had pulled up our family history, taking note of various family trauma and previous mental health incidents I had experienced nearly a decade before. I have no clue where this information is stored, why they need it, or how they got access to it, but 'they' have it, and 'they' use it. It was in this moment that I began to think about social media and all of the data circulating around it - like the airport, I was being surveilled like the panopticon, being watched with the most careful of eyes by a guard in the tower.

The panopticon comes from a prison design by Jeremy Bentham in the seventeenth century that situates its prisoners in a circular formation surrounding a central watchtower. This is done in order fo the few to exercise their power over the many. The prisoners have no sense of privacy; consistent surveillance renders them powerless to those watching. Perception is essential in the function of the panopticon, because more than actually surveilling the prisoners, the central watchtower makes it so the prisoners feel as though they are being watched. This feeling creates docility amongst the prisoners. The true power of the panopticon comes when there are no guards in the tower but order amongst the prisoners is maintained; where the feeling of being watched conditions self-regulation. The imposing nature of the tower itself breeds the architecture of surveillance. This architecture has become omnipresent outside of the prison now. From chain link fences to closed-circuit televisions to law enforcement, there are structures to remind one that they are being watched all around.

Philosopher Michel Foucault takes Bentham’s panopticon and analyzes its inner-workings, applying its ideals to notions of power through surveillance. Contemplating issues of panoptic states, Foucault discerns three criteria necessary for the panopticon to function outside of the prison: to impose power at the lowest cost, to exercise social power through surveillance, and to place that social power as a primary source of human functionality. A visible yet unverifiable power is key to maintaining the panopticon. Aesthetics of power become essential for this to work, as these forms must be easily recognizable and suggest consequences upon being “caught,” so to speak.

One of the most present cultural institutions in all American cities that enforces this panoptic state is the art museum. The art museum serves to connect visitors with works of art; exhibitions are organized by curators of the museum, who choose works from collections in order to convey a point of view. Through the act of placing work throughout the museum space, both the art and the curator become the de facto experts on the subject being presented. Museum-goers must be wary of this submission of power and enter an exhibition with a critical eye to the selection, organization, and works on view. An exhibition is a zero-sum game, where the fact that one work is on view automatically means another is not - the curator is in control. There is no perfect solution, as there are many more works of art than there is wall space in the world. Viewers must exercise their power in order for the museum hierarchy to be partially dismantled.

However, this becomes next to impossible due to the architecture of the panopticon present in the museum space. Due to the monetary value ascribed to works of art, museums are monitored by security cameras and oftentimes guards physically in the space as well. This is not kept secret by institutions, purposely letting visitors know they are being watched in order to maintain the idea of museum etiquette. If not instilled by an authority figure upon first visiting a museum, the rule of “no touching” is quickly implemented by the architecture, attitude, and law enforcement at the museum. In some institutions, lines will be placed on the floor in front of certain paintings and sculptures in order to tell a viewer how close they are allowed to get to the work. Some have sensors that, when triggered, produce an alarm. Consider this a watchtower with a guard. This museum panopticon can be partially dismantled with the intervention of specific artworks in museum spaces.

Without art, there is no museum. This relationship is essential for artists. Especially in contemporary art institutions, artists can invert the didactic hierarchy between curator and viewer. This is where the panopticon can be either smashed or reinforced, often regardless of the intent of the artist. Artworks that emulate the violent architecture found in a panoptic society, often made to critique, can heighten the museum panopticon. The empty watchtower becomes a sculpture-like object, with a commanding power over the viewer’s psyche. Outside of the panoptic prison, imposing forms are constructed by a more powerful class in order to manipulate society.

These ever-present pieces of violent architecture become the inspiration for artists appropriating these forms in order to subvert their power. The sculptures Not yet titled 1994, and Untitled 1999 by Cady Noland, specifically through their exhibition in MONO: Oliver Mosset and Cady Noland at the Migros Museum in 1999, embody this idea. So does Policeman 1992/1994, by Duane Hanson, and its two placements in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and lastly, Untitled 2014, by Tom Sachs. Each of these sculptural works places the viewer in a state perceived directly by the panopticon, a space that allows breaking free with no fear of punishment.

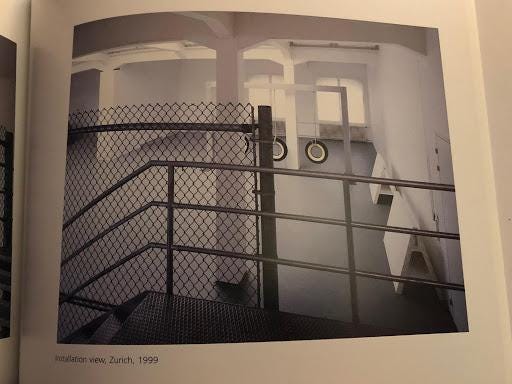

Cady Noland’s oeuvre of sculptural works is rooted in a critique of the brutality found in American objects, ranging from guns, newspapers, and chain link fences. In reimagining these forms with new materials, Noland is able to draw attention to the subtext within these seemingly mundane objects. Both Not yet titled, and Untitled, are examples of Noland’s ability to re-contextualize the quotidien form. Not yet titled is comprised of a 120” x 149” chain link fence, the same kind of fence used to close off areas where one is not allowed. Whether an active construction site, prison, or private property (One of Jenny Holzer’s truisms comes to mind, “Private property created crime”), the chainlink fence exists to keep someone out. The fence represents a choice of where one can/cannot go as it is exercised over others. While the physical barrier is not an effective way of keeping people out, fences can easily be cut open and climbed over. Yet, the fear implied with breaching such a barrier reflects panoptic qualities in a fence. The installation of Not yet titled is key to the critique of panopticism.

The work is flush with the staircase leading into the gallery of Noland’s work. At the top of the staircase, the viewer is unable to see all of the works on view although their view is unobstructed. As one descends down the staircase, the chain link begins to tower over them and obstruct their perspective of the other works on view. This placement is essential to breaking the panoptic quality of the chainlink fence. One is only briefly kept out of the space, and upon walking from the stairs, the work no longer keeps one out, but invites them in for closer consideration.

Once they pass Not yet titled, the viewer encounters Untitled, a minimal work comprised of elements of police barricades stacked together. These barricades have been rendered functionless, as there is only one middle part supported by far too many end pieces of the barricade. This brings new light to the form, making it look excessive, which draws attention to the frame. The inspiration for this work by Noland is taken from the photograph Pushers and junkies put massive pressure on the Langstrasses neighborhood in Zurich. The answer was massive police pressure, by Livio Piatti.

The photograph depicts police officers writing tickets to civilians behind a police barricade. Notions of keeping out become present again, now in how the sculptures protruding from the wall produce a phallic form, aimed to be a commentary on the hyper-masculine associations present in policing. The entire barricade is white, stripped of any didactic text, leaving only the object. The text on the barricade is essential to effectively keep people out, often reading “danger” or “Police Line Do Not Cross.” If one is unable to understand the delineation of the physical barrier, they are held accountable to read it, too. The police force provides some of the best panoptic architecture utilized for controlling masses of people. Better than their architecture, the presence of a single police officer can do the same work as the empty watchtower.

Duane Hanson creates hyper-realistic sculptures of human beings. These lifelike forms intervene with viewers’ interactions of traditional art spaces. Viewers will often get too close, even touching the works to verify whether or not it is a live person or a sculpture.

Policeman is a seminal work in panoptic aesthetics. Police are liaisons of enacting the panoptic state, working as the watching power with added legal power to exercise consequences if laws are broken. The police visibly carry handcuffs, batons, and guns; these weapons loom as the bodily consequences if one is to break the laws. This fear instills self-policing among citizens, so the presence of a singular police officer in a space will alter the behavior of large groups of people.

Upon the San Francisco Museum of Art’s remodeling and reopening in 2016, the curators of the institutions’ placement of the work activated their panoptic qualities. Policeman was exhibited adjacent to the staircase on that floor of the museum. The sculpture, situated against the wall, was often missed by visitors using the staircase. This is due to the realistic qualities of the form, complemented by its placement, eluding that rather than a work of art on view, the sculpture is a police officer monitoring the space. The work has since moved location in the museum, now situated in a small gallery dedicated to hyperrealist sculptures . However, in this exhibition, Policeman is sanctioned not only by a border of tape, but functional alarms set to go off if one gets too close. If that is not enough, the museum staffs a live guard in that space to reprimand viewers who break the institutional rules.

The closed-circuit television (CCTV) has become a defining fixture in surveillance to ensure order. Infamously, the United Kingdom has a staggering one CCTV for every 32 citizens. These surveillance cameras are positioned all throughout cities and were done under the guise of reducing crime by using the footage from the cameras to catch criminals. The false CCTV is the evolved form of the empty watchtower in the panopticon, instilling the same fear with a much smaller and invasive piece of technology. Here, the CCTV has become iconic, ripe for appropriation and critique by artists. Using everyday materials his works, bricolage sculptor Tom Sachs gives new light onto recognizable forms from pop culture. Sachs’, Untitled, is a CCTV camera fabricated out of plywood, fiberglass, resin, hardware, and bamboo. Sitting atop a plywood base, Sachs situated the CCTV camera below the viewer.

This choice subverts the physical hierarchy of cameras’ high vantage points in order to better record an area. The materials used to construct the camera also work to invert the power held by the CCTV. Using low tech materials, the CCTV is no longer able to function with its original intention. Lacking the technological makeup to record, it becomes similar to false CCTV cameras installed with the same purpose of functioning ones. The false CCTV cameras are nearly identical to the empty watchtower, they cost marginally less while producing the same results from surveilled citizens. The materials lend themselves to produce a more human quality to the form. Marks on the surface from mistakes made while constructing the sculpture are left to visually indicate the process of construction, the drips of resin elude a human imprecision, the CCTV now prides itself in its flaws. Rather than a camera, the CCTV features a small mirror, so upon closer inspection of the sculpture, a viewer will see themselves. Sachs shared an image of the work on social media amply accompanied by #panopticon. This iconic panoptic form is rendered to work with and reflect human beings rather than attack them.

Foucault’s idea of a panoptic government and society has become our reality. In all aspects of our physical and digital lives, we are met with panoptic devices. Self-policing and docility are used against the powerless masses. Through appropriation, reduction, and re-contextualization of panoptic forms, artists are able to guide viewers into thinking critically about their surrounding panopticon. However, these experiences exist in a panoptic museum vacuum, which is seldom criticized by the artists showing that space. Knowing of the panopticon does not stop it, Foucault does not provide any solutions either. As a viewer and a citizen, these panoptic devices become overwhelming in any space. The arts may not be the solution, but the education of these surrounding objects and institutions is a productive beginning. Once aware that we are victims of panoptic devices, we may begin dismantling it. If we do not, we will not be free.