Op art

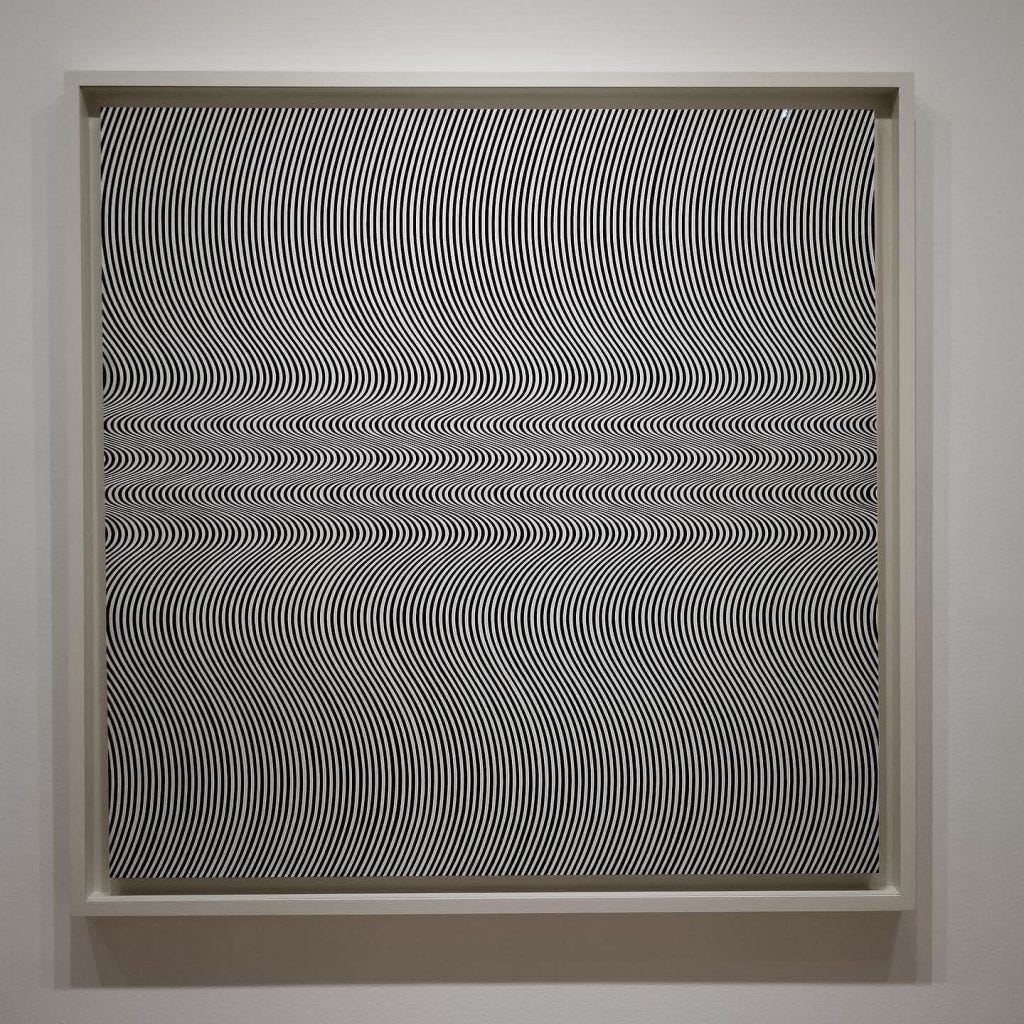

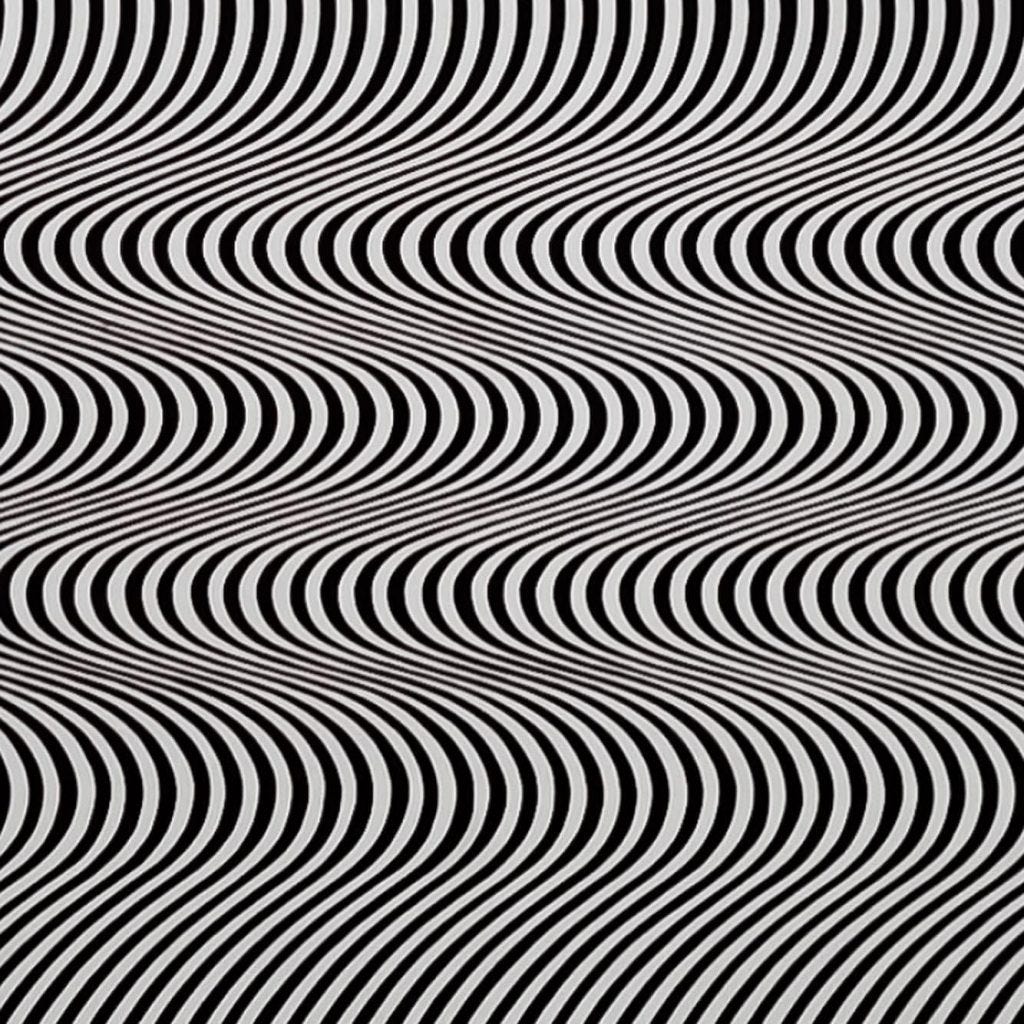

Like most movements of the ’60s, Op had its own politics. It proclaimed a direct appeal to the senses—anyone’s senses, not the rarefied gaze of connoisseurs. “Art is the plastic aspect of community,” Vasarely wrote in 1953, long before Op as such existed. The Op “democratization of art”—Vasarely’s phrase, the title of his 1954 manifesto—remains steeped in a “positivist” attitude toward technology, and the movement remained explicitly attached to ideas of progress. But how do these communitarian and technophile impulses square with the discomfort/vertigo question? Does the radicalization of content presuppose a radicalization of form, as it did for Berlin Dada, Futurism, and Russian Constructivism? Does the visual overload/overkill of so much Op art (Boriani’s “psycho-sensoric infuriation”), its pointed destabilization of “normal” vision, correspond to a potential rupture in established modes of social and political address and behavior? Op art stands at the intersection of these contradictions, its positivist belief in technological progress bluntly opposed by the pain inflicted by many of the artworks, and the concomitant, acute sense of perceptual and bodily disequilibrium they induce, from Riley’s Current to Boriani’s stroboscopic room. This is the true politics of Op, quite different from its ostensible program. It accords with profound epistemic rifts within the broader culture of the 1960s. Op is the nonobjective correlative of psychedelia, the promise of a realm of vision and experience beyond the accepted protocols of quotidian existence. But its potential, historically understood and as an early twenty-first-century “revival,” depends on its capacity to alert the viewer to what he is already experiencing, even though he may not be conscious yet of what exactly is going on. The pain and disequilibrium that are absolutely constitutive of Op—the way it rattles the cage of “everyday life”—point to what isn’t future-fantastic in our technocratic and media-glutted modern world. Utopian dreams brush constantly against dystopian dread; dysphoria follows euphoria as today’s hangover follows last night’s cocktails. Headache and party fuse.