Interview with Devon Turnbull by Bilal Mohamed

Photo by Isa Saalabi

Devon Turnbull, founder of Ojas, a high-end audio company, co-founder of the late menswear line Nom de Guerre, audiophile, designer, sound guru, amongst various creative titles and aliases, took the time to discuss in depth his obsession with sound and music, traveling the world in a World War 2 era German ambulance truck, and about his close friendship with the late Virgil Abloh, sharing many of the valuable lessons he’s learned from him.

Turnbull currently has an exhibition on view at Lisson Gallery in New York (June 29 – August 5, 2022) and his speaker systems are concurrently featured in Virgil’s retrospective “Figures of Speech” at The Brooklyn Museum (July 1, 2022 – January 29, 2023).

Devon Turnbull: My home situation is a little crazy right now with the show going on. It was kind of like a full takeover, you know, like I had to produce so much stuff in so little time the house just fully became my studio.

Bilal Mohamed: I know that feeling. Well, how’s it going besides that? Everything good?

DT: It’s going great. You know, it’s been extremely busy with the show up and I didn’t think I was gonna have to spend all of my time there. But yeah, my wife’s been teasing me because I have a full-time job right now. Like I just have fully committed to this. It’s just that I learn too much and I think the experience is too valuable to not be there all the time. So it’s been a unique summer, so far.

BM: Well, it looks amazing, man. And then you got your work showing at The Brooklyn Museum as well, right?

DT: Yeah. And I’m excited to activate that as the Lisson thing mellows out because I really want to spend some time over there as well.

BM: Hell yeah. Before we even get into anything, just for people who don’t know of you and your work, could you give a quick spiel about who you are, where you’re from, and what you do.

DT: Yeah. So my name is Devin Turnbull. I kind of operate creatively under the name of Ojas, which is sort of a creative pseudonym I’ve been using since I was quite young. It was sort of my graffiti nom de plume at one point. I had studied audio engineering when I was young, that was my major, and that was what I thought my career would be. But you know, I was just kind of fucking around with side projects and creative stuff that I didn’t think was potentially anything serious, you know? Like I started making some clothes when I was still in school under the name Ojas as well. When that kind of took off I wound up co-founding a brand called Nom de Guerre with some partners – Isa Saalabi, Wil Whitney, and Holly Harnsongkram. And so, you know, at that point, audio and music sort of just flipped from being what I thought was my career to then visual art. Visual art and design being my hobby, I kind of turned that upside down and for a decade or so, became a full time designer, for lack of a better term. Basically designing various things. And audio became kind of my passion project. I re-contextualized the way I listened to music from going out to listen to music and playing music for people in venues to listening to music at home, and then, listening to music at home became something I took very seriously. So I kind of organically grew this practice of building high-fi listening equipment myself, and that eventually matured into what my current creative practice is. For the last 10 years that has been my primary creative output, which is sort of bespoke audio, reproduction equipment – stuff that we use to listen to recorded music.

BM: For someone who might not be interested in speakers or audio equipment, why would you say the quality of sound is important? For example, what is the difference between using a $200 Bluetooth speaker and the speakers that you make and are accustomed to.

DT: Yeah. I mean, that question is obviously something that we talk about a lot, and in context. Like perspective is quite important when having that conversation, because I get asked about that. Like what is unique about this stuff that you are building all the time? And I always need a little bit of background from the person as to what their perspective is before I can accurately answer or like, you know, answer the question in a way that’s relevant to them because the kind of equipment I make is, particularly in the United States, a very unusual approach to high-fi music listening. That specific kind of technology, not just using tubes, but using a specific type of tube called a triode, big high efficiency speakers. And it’s a unique sound compared to what you’ll hear if you go to a conventional high end audio showroom. So there’s one context, what attracts me to the kind of stuff that I build compared to high end audio, and then there’s what attracts me to just listening to music. I think to answer your specific question compared to a $300 Bluetooth speaker… I guess there’s really two primary components that I think are essential. First and foremost, you know, regardless of my sort of system versus someone else’s, is just creating an environment which is sort of like a shrine to music. Creating a space where listening to music is your activity, your primary activity, as opposed to something that you do passively, like in the background. You know, even Sonos, for example, who, and like I’m not here to knock on Sonos. I like Sonos. I work with Sonos, their whole thing that’s made them really successful is that what they do and other brands like them do is try to create an easy way of making a large multi space location have music playing everywhere. And it’s kind of by nature in that sense background music, right? Like the technology and in a lot of ways, this started with some of the Bose stuff that was introduced in the eighties where the idea was like, “Make this thing almost invisible.” And you know, by nature it is usually used for like background music and I think the same is true for a lot of the little portable Bluetooth things. You stick one here, stick one there. And it’s just like, it’s easy. I can have music playing and I can go about my day with music playing and it sounds pretty good.

BM: I remember reading a quote from you in another interview that basically said, “It’s the difference between watching a movie on your laptop versus watching a movie in the theater”.

DT: Yeah, that concept has even kind of evolved since then. And I know this is kind of an extreme way of putting it, ha-ha, but it’s like going to the movies to watch a film versus what works on Tik-tok. You know what I mean? Like, not to say that, like a pill speaker or whatever they are, is like the music equivalent of TikTok, but like that is a literal way that some people listen to music. And for a lot of people these days in popular music, that is the goal of certain types of pop music now. It’s like, “we want to be a viral TikTok video,” right? That’s like one form of success for a musical artist. That’s not the kind of experience that I’m looking for in listening to music. You know, most of the music that I listen to is like albums for one thing. Music was much different in the stereo era when pretty much everyone that considered themselves a music lover had a home stereo and a place to sit down and listen to music. And I think there’s a lot that’s happened in the 20 or so years that’s led to the way people listen to music now. But I think streaming is a totally valid way to listen to music. There are very high quality streaming platforms available now, and you can build an amazing system around that type of listening. But for me, it’s even just something about the action of sitting down with an iPad and searching all the music ever made and hitting play on something. I think that just even that in of itself has affected what people are listening to and how they’re listening to it. There’s something about the physicality, even if it’s just a CD, like sitting down with the album art. I mean, it’s pretty universally accepted that you could stream music these days at a higher quality than a CD, although there are some great sounding CD players. But I just mean that, there’s something about the physicality of the medium that I have a relationship with the music.

BM: Even in that regard, I don’t think people buy CDs or buy records as much. So, naturally, musicians are probably making far less money.

DT: Yeah, I think that these days, the name of the game in music is like merch and stuff because people don’t consume music in the same way and I think that’s a shame, you know?

BM: One hundred percent.

DT: It just really takes away from making masterpiece music and encourages more brand building than music thinking if you know what I mean?

BM: Yeah. I agree. I know this is kind of a bizarre question, but have you ever spent a long period of time without music, like without listening to music at all?

DT: For sure. I mean, just by circumstance. Like, if I go and I’m traveling. You know, obviously you can have great experiences listening to music on headphones, and sometimes when traveling, you have really cool listening experiences on a plane with headphones on, cause that again puts you in this, like – Anyway, that has nothing to do with your question.

BM: No, no, actually that’s another question I had, like about listening experiences. Like musical memories you have where it’s like, you were in this specific place at this specific time, you know?

DT: Oh yeah. Set and setting is like everything with music and music triggers so many things, including memories – and I’m not unique in this way. Like my ability to remember facts, numbers, names, things like that. And this is all people pretty much universally – like you can hear a song and remember lyrics that you would never remember word for word if it were not set to a melody. Like you can hear one song, one time. If it’s catchy, one time and you can remember the exact combination and order of words. Like if I just told you, “Tomorrow you’re gonna see someone and tell them, “The elephant walked through the Sahara and drank some water,” in those exact words. Tell them that tomorrow, you’d have to write it down. But if that were the chorus of a catchy song, you’d have no problem remembering it, you know? And it’s like the way our brains work. Music affects our brains in amazing ways. And I think of music often as being more profound than a drug. There’s a lot we don’t understand about the human brain and I’m certainly not a neurophysicist or know whoever would know more about it, but it’s just something incredible about how frequencies are just circling through the air, hit your eardrum, and make your brain feel certain ways. And then to just get even more trippy about it, it’s all mathematics and physics. Like the fact that when the frequency of that vibration in the air doubles, so when you go from 200 Hertz to 400 Hertz – in other words, there are 400 vibrations per second versus 200 vibrations per second. We perceive that as an Octave. Like that kind of stuff I just start to trip out on super hard. You know what I mean? Where like there are mathematical things happening with vibrations in the air that our brain perceives as harmonious or not.

BM: Wow.

DT: There’s just so much about the way sound affects the brain. That yeah, you hear a song and you think of an experience you had, you know? There’s not a whole lot that has that ability to reprogram your brain, and that’s why it’s so important, if you feel compelled to do so, to build a practice around listening to music. There are a lot of religious practices where singing becomes part of like your religious practice, like Vedic Hindu religion, where getting together as a group and harmonizing and singing becomes like a meditation. But, you know, I just think that with the way technology and music have gone, we’ve lost a lot of valuable experiences like that. So, not to say that I’m like a genius and I came up with a unique way of listening to music that’s gonna reprogram your brain, it’s just, make a practice of listening to music and in an intentional way. I think with the vast majority of our friends and peers within our creative community, it’s obnoxious to say, “oh, music is important to me” because music is the foundation of so many people’s creativity. So whether it’s an art studio or design studio, or you’re making food or whatever it is, for so many people music is an essential element. And I just try to encourage people to take that seriously.

BM: What are some things you’d say you’ve learned from being a multidisciplinary artist rather than – I mean, in some way you are specialized, but because you’ve done so many things at this point?

DT: Yeah, that’s definitely a fair question. I didn’t really understand what a multidisciplinary creative was at a point, you know when I was younger, and I guess very young, like in school – this is 20 something years ago. I’m 42. Going back 23, 24 years ago when you’re in school and you’re like, I have to pick a major, I have to do something. I gotta figure out what I do. You’re kind of programmed to think that. This whole multidisciplinary creative thing is sort of a new thing. For example, whether it’s like, okay, I’m going to commit to writing graffiti for a period of time and it’s like, people will think I’m a toy if that’s not all I do. Back when I was designing clothing, we started Nom de Guerre in 2003, I think I did get a lot of criticism for not being like, “I’m just a clothing designer.” You know what I mean? Like the, the industry was still not really ready for like, “No, this guy’s something else other than a clothing designer, he’s a creative and he’s making clothing. He didn’t go to FIT, he’s not draping.” The audio thing, I initially just wanted that to be my personal work and not make it into a public thing so much, because I was like, “I don’t wanna fall outta love with this.” I just wanted to keep doing this until I’m old and gray and I wanna make sure that it remains my passion and as people started getting more and more interested in it, I felt like I had to kind of hide the fact that I had all these other creative lives prior to doing that because people won’t take me seriously in this world, unless I’m just a dude in a lab coat. I’m an outsider in the audio world. I still am for sure. I’ve definitely managed to establish really valuable relationships with most of the people that I look up to in that world, but there’s no getting around the fact that if you read about me in the audio press, it’ll be like “This guy totally isn’t coming up through the usual channels that one has to come up through.” For a long time, I felt like people won’t take me seriously unless my other creative pursuits are sort of a secret. And it was definitely Virgil who – I mean, I told him I don’t know how much I wanna connect the dots for people. I feel if people are gonna take the audio work that I’m doing seriously, and for sure that is true of some kind of older, biased, conservative audio consumers, they’re going to discount my work based on the fact that I’m not whatever that is, but V was just like, “No, man, you’re going about this all wrong.” Like it’s all about building a layered universe of creative stuff, not limiting yourself to what your output can be and just putting them all under one umbrella. He just explicitly told me, “This is not your weakness. This is your strength.” Like you need to embrace the fact that you can design graphics, write about this, and design a circuit for an amplifier, and do carpentry and wire up an amp and do all these things. He’s like this just makes your work so much more interesting and you should embrace it. I think for me it kind of clicked at that moment because I realized that what I do in audio really is the perfect culmination of all these different things. Like I have a great team and a lot of consultants that I work with when I need to, in various ways when designing audio, whatever it is, whether it’s a speaker, an amplifier or a turntable or whatever, but I feel very fortunate that I have foundational skills like graphic design, for example, which you wouldn’t think applies to that, but I use it so often in any number of ways. So I feel like lucky that that has been my path.

BM: Would you say you find it important to be accepted by the audio world? Because I feel like from the outside, it seems a lot of the people interested in your work are more so the fashion people, designers, the writers, or artists. But I mean, that’s just from the outside. Would you be satisfied with that kind of audience rather than, you know, the professional audio types?

DT: No, I mean, I’m first and foremost interested in the way my stuff sounds. Like, although the aesthetic of it is important, it’s 100% form follows function. And the thing that motivates me 100% of the time is the sonic effects of what I’m doing. So, you know, it means a lot to me that I have the acceptance of, for example, engineers that I look up to. And people who – for example, Mark Ronson, is an important customer of mine, or consumer of mine, whatever you want to call it. I mean, yes, he’s become a friend as well, but he’s someone with a very well trained ear that the way we met each other and developed a relationship was strictly through his attraction to the sound of my stuff. And he’s someone who’s not interested in HiFi for HiFi’s sake, and doesn’t follow HiFI industry trends. In fact, he had a system which was more on trend in the high end audio world. And what I do is in a lot of ways an antidote to people who are kind of exhausted by the way the high end audio industry continues to cycle through technology and try to make yesterday’s technology obsolete. One of the things that attracts me to the type of technology that I utilize is that it’s timeless. A lot of the stuff that I make is based on sometimes 80-90 year old technology. I’m much more inspired by, and just strictly because I enjoy the sound of mid 20th century audio technology – I just find it hugely relieving to listen to that stuff. Like when I discovered that as an approach to system building I found it as a huge relief that you don’t have to be on this hamster wheel of like new stuff all the time like, oh, now there’s a higher bit rate, now there’s a new speaker that can go higher or that can go lower. It’s like, oh shit, this stuff sounds amazing and this 50 year old speaker sounds so much more relaxing than the stuff that I’m hearing when I’m going to a lot of high end audio dealers, you know? And I am looking for a different kind of music listening experience than a lot of those consumers are. I talk a lot about posture when listening to music. And when someone comes into one of my rooms and listens, if they sit down and they look kind of like serious and are trying really hard to develop some kind of articulated opinion on how the thing sounds. I’m always like this guy’s not doing the same thing I’m doing. I want someone to come in, start listening, and if they’re gonna sit forward in their chair, it’s because they’re like, “Wow, this, this feels really sweet and I’m sparked by this”, but I really want people to just be relaxed with the music.

BM: Just let it flow through them.

DT: Yeah just let it flow through people and have them settle down. It’s like a calming thing. I wanna listen to music and I want, when the record ends, I want to kind of be stuck to my chair. I want to be like, I need to take a moment, I’m too relaxed –

BM: I think that’s something special, man. Because in my relationship with speakers or people who invest a lot of money in speakers, I’ll always think about my uncles and my cousins when I was young, who would buy these crazy speakers for their cars and talk so much about it, but you hop in and listen to it and it’s just painful to listen to. It’s just like this crazy noise, you know?

DT: Yeah. I mean, I think the opposite to an extent, like car audio, for example – at least it’s people having fun with sound. You know what I mean?

BM: Yeah I feel like people don’t anymore, Like it’s not that serious.

DT: Yeah. Mm-hmm. Even if your whole thing is car audio, culture was for sure, when we were young and I’m sure in many places still is, just about making as much bass as you possibly can. At least through that practice. You’re learning about how sound works and kind of having fun with physics. You know what I mean? I wouldn’t call it music listening but at least its a really cool way of introducing people to the physics, acoustics, electronics of how sound works. I can think of worse ways to spend a Sunday.

BM: Right, ha-ha. I did wanna talk a bit about your van life. Not sure if you’ve been into that lately, but I’ve always been super interested in it.

DT: Awesome, yeah, you never know, like sometimes it comes up and someone’s just like “You, what??” I mean, I love it. It’s definitely another passion of mine. I’ve been too busy for the last, well, through COVID just by circumstance, like when COVID set in a lot of people were like, oh man, you guys are all set up, you guys must be loving it. You’re just traveling around in your van or whatever. And it’s like, actually that was just by coincidence, that was not our situation. We had one fully built camper that’s in Europe and we couldn’t get to Europe for like a year.

BM: Oh, that one’s out there? I didn’t know that.

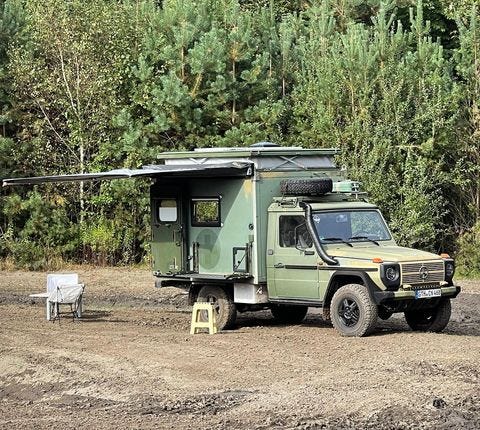

DT: Yeah, so the main camper we’ve been traveling in the last four or five years is a Mercedes G class ambulance that I bought from the German army.

BM: Yeah that thing is sick, so tight.

DT: Yeah. Thank you, I love that truck. I mean, it’s not in so many ways. It’s totally impractical. It’s super slow, it’s super noisy, but it’s fucking beautiful. And it’s so simple. And now we’ve done a lot of work to make it less underpowered but it’s just so simple that even I don’t have a great understanding of engines and how to make cars work, but even I can figure out how to fix most of the shit that happens on it. It’s just like a lawn mower, you know, it’s like a big lawn mower. It’s just a tiny diesel engine and is super efficient and super simple and has so few things that can break on it. And it really is like the purest type of vehicle. But yeah, I bought that thing from a salvage yard, more or less. A place in the south of Germany that was selling airport equipment and military stuff and they had these three army ambulances, and I bought one. And I just thought, like, I’m just gonna go full handmade, tear out the ambulance stuff in this box and make it into a camper, and it wound up being an insane amount of work. It was like, six months, pretty much hardcore working on this project. tf eventually got done and my wife and I drove it from Germany, made our way down to Morocco and spent some time in Morocco, just driving all over. Pretty much the whole country and then back up to Germany. We did a full replacement of the engine with a slightly more powerful eco engine. But that was the year before COVID where it was like having all this mechanical work done. And COVID hit and we got separated from it. I bought another truck right before COVID and left it in LA and I was gonna go back and forth and keep on fixing it up myself. But you know, during peak COVID you couldn’t go anywhere.

BM: What would you say are some of your favorite places you’ve gone so far?

DT: Morocco is incredible. I mean if you’re just trying to experience the natural world, California, Baja California, and Mexico, like that whole stretch of the Pacific coast is amazing. I mean its obvious but like California just has so much biodiversity. From the north to the south, you’ve got the change in climate, the Sierras, you’ve got high Alpine, you’ve got the coldest and the hottest places in the United States. You’ve got places that are super fertile, you’ve got the desert, it’s very fun. But, you’re in California. It’s like, Morocco has that much biodiversity, but you’re in Africa. It’s a whole different culture. There’s so much more to just like getting food, you know? You’re gonna discover something new. I mean, we saw produce that we’ve never seen otherwise. Just little things like that. And also, for me, traveling is a lot about getting out of your head space. I like to just get lost – like we’re talking about, taking a week or two in August to go somewhere. And the G wagon is in the north of Germany right now. And I’m like, let’s just go somewhere. Because you know, Europe is so crazy during August. Like anywhere thats a tourist destination is a wrap. But yeah we’re talking about like, just go pick it up and go up to Scandinavia or go somewhere kind of like random. Because that’s one of the things that I love when I’m traveling is just looking around at the people around me and being like, where the fuck am I?

BM: Yeah and then you come back and it just feels like, what even was that? Like, it doesn’t even feel real.

DT: Yeah and it makes you see your home environment differently, broadens your perspective. And I love having that sensation of being amongst people, but I’m like, man, I don’t know how these people are perceiving the same situation that I’m in right now – I can’t call it. I think a lot of people have that experience when they go to Japan. because the culture is so different. And I think Morocco is the only place I love. Also traveling in Latin America, but because the United States of America and Latin America are actually connected. And there’s so much Latin American culture in the U.S. as well. It doesn’t feel as much like you’ve gone to the other side of the world.

BM: Really? That’s interesting.

DT: In my experience, you know, my wife is also from Puerto Rico. I spend a lot of time in Puerto Rico. So I’m around Spanish a lot. I would just encourage people as much as possible to just get out, you know?

BM: I agree, man. I agree. What got you interested in the first place? Like how long were you doing this for? You were doing this before COVID yeah?

DT: Um, what year was it? Let me look at – this is how I remember dates – I like go to my iPhone photos and just go to like a place that I know I was at a long time ago and I see when it was… So I guess in 2015 is when we really were going with it. So it was like 2015 to 2020 we were doing a lot of that kind of travel. You know, the way I got into it originally was like, cuz I grew up skating and snowboarding and surfing. So I have a lot of friends out west, and it’s a much more common kind of lifestyle out there, right? Especially nowadays, but even back in 2015, I think that was just starting to become a trend and most of the people that I knew of that were doing it were people who were doing it to access the outdoors. Like, you know, people that would chase a swell that’ll be like, I live in San Francisco, but there’s an amazing swell coming, but you have to be down in Southern California and they would just go down and post up. And I was just like, man, people are so lucky out there. They have so much more access to stuff. And here, there’s just such a high density of people that there aren’t very many places that even if you have a van, you can just go and enjoy in that way. So when I was young, my parents had a house out in Amagansett. My dad bought a place out there in like ‘83. So I kind of grew up my whole life spending a good amount of time out east on Long Island. And my parents eventually sold that house. And obviously like the east end, particularly like the Hamptons super un-accessible financially, if nothing else. So that was like, all right, that’s a wrap. That was lucky, but we’ll never be able to do that again. But I remember when I was a kid, always seeing campers driving out to Montauk and being like, where are those guys going? But in the fishing community, it’s always been a thing. There’s an association called the Long Island Beach Buggy Association. And basically I started digging in I’m like, where the fuck are those guys going? So there’s this organized group of short casting fishermen that have been accessing and maintaining the ability to access remote beaches out there with four wheel drive campers. And because a lot of fishing is a night activity, they’ve as a group, been able to lobby and maintain the right to drive on these beaches, remote places and just camp on the beach. And I was like, all right, I’m in, how do we make this happen? So I built the first camper we had in, yeah, like 2014 I guess. And just then by circumstance, we, my wife and I had, just because of the way things were happening for us professionally, we kind of had a lot of time. And instead of looking for new opportunities, we decided to kind of buy time and just travel that way a lot more.

BM: Yeah I was curious about that. Because it’s so easy to find a reason not to do something like that, you know?

DT: Absolutely.

BM: Cause you feel like you’re missing out, you know – the FOMO.

DT: And even for me right now, like through COVID because our only camper was unaccessible due to travel restrictions I just doubled down and started working a lot, you know? And COVID was unique, my circumstances were really unique because my thing is really home audio. I didn’t even know, like, it was like week one of COVID, we didn’t know what was happening. We didn’t know if this was gonna last two weeks or two months or two years? Two years was inconceivable. It was like, “it’s gonna be a couple weeks, maybe a month.” And I remember, I think week one of COVID and I’m sure that Virgil was having a lot of meetings with smart, strategic marketing people, and they’re like, what does this mean? Like, what does this global moment mean? But he hit me up week one. He’s like, “It’s time.”

BM: “Now’s the time.”

DT: “Now’s the time,” yeah. Now’s the time and I was just like, shit, yeah. I think you’re right. But you know, it hadn’t even crossed my mind. He’s like, “You gotta go, like, you gotta hit go right now.” This is a window of opportunity. And then I sort of conceptualized the kit building thing because I couldn’t really hit go as we didn’t have a team in place cuz everyone was staying home. And I was like, okay, we could probably make just parts with just one or two people. And the whole DIY thing was – think early COVID, you know, like people were baking their own bread instead of –

BM: The bread, ha-ha. I remember the bread.

DT: Yeah. Bread baking. And I was like, why am I making sourdough bread? Why don’t I build some speakers? And I’m like, I bet some other people would do this. And it just really took off. So you know, I’ve had a lot at a time when most people were, you know, when their practice was shrinking, when their businesses were struggling, I had a really unique moment of opportunity.

BM: That’s beautiful. Yeah. I feel like that’s how it was for everybody. Like either things fell apart or they just skyrocketed.

DT: Yeah, it’s true. It’s true. And you know, you can only count your blessings. But you know, I’ve kind of gotten to the point now, too, where like we did one trip in the fall of last year. I went out, like I said, I had this big truck in LA that I was working on building and it was almost done. It was done enough that we could use it a little bit and I wanted to get it back to New York. So, my wife and I went out to California and drove from like San Francisco down the coast to San Diego and then drove back here from there. So that was our one trip in the last two years. And we were on the road for a few weeks and it felt really good. But it’s hard. It’s become harder for me to justify taking the time to do that kind of stuff. But I wanna make sure that it remains a priority. I was pretty dead set at one point on driving around the world, like, doing the whole circumference.

BM: Damn.

DT: Yeah and like doing it in pieces is important cuz I’ve never stopped working. I’ve never stopped. Like a lot of people in that world they’ll like sell everything, figure out how to make money passively or remotely but I’ve never done that. We’ve only ever done like 50-50, at most, so it’s like, you know, we’ll drive, like we did a big trip in Mexico. I think we were in Mexico for over a period of six months, I believe. But the way we did it was to drive from New York to San Diego. Keep the truck in San Diego, come home, fly back, drive around the Southwest a little bit, come home, fly back, drive down Baja, take the ferry to Mazatlan, drive down to Puerto Vallarta, find somewhere to store the truck, come home, work, go back. We made it down like almost as far as Acapulco and it just got too hot. So we started coming back and we had some homies then that wanted to come down and do part of the trip with us. And, you know, it was a lot of surfing and it was awesome.

BM: Awesome. I did want talk a bit about Virgil. I know we talked a little bit already, but I’m just curious, as you know, he’s taught us so much over the years and I want to know if there’s anything you’re implementing or have implemented since he’s passed that is helping push his legacy forward or your own things that you’re trying to use in your own life that you’ve learned from him.

DT: Yeah, of course. I mean, he changed my life professionally, probably more than anyone ever has. You know, like I said, I mean, first of all, just his kind of contextualizing all of my different interests into one, like he basically taught me what a multidisciplinary creative was and that was a thing that you could be. I also burnt out super hard on the fashion industry at a certain point. And, I just wanted nothing to do with it for a long time. It took him like a couple years of like, “Come on, let’s do this, let’s do this, let’s do this,” before I was like, all right, you know, I can kind of get back into this. And he just made it so fun, you know, even before he had the LV thing. Even before, I had checked out. And when I had checked out, like, I mean, I really checked out, like I just totally stopped paying attention during the rise of Off-White. I mean, I was friends with Heron from like a really early age. So I was aware that these guys were doing something and that it seemed to kind of break through some glass ceilings, right. That they were achieving – they were doing the same practice, but they were gaining and accessing pop culture in a way that wasn’t possible when we were in earlier years when New York downtown street wear was still pretty underground. And then even men’s fashion industry wasn’t really a thing. Like when Nom de Guerre was trying to make menswear, we realized at a certain point that all the brands that we wanted to emulate, if we got into every single door we wanted to be in, you still wouldn’t be able to make a living doing that. And that had changed after I’d checked out. You know, I knew that that the business had grown immensely but I still didn’t know what his legacy would be. We just established a friendship and I don’t know where he sits in this whole thing, but he just is such a good person that he’s the one person that I’ll be willing to work with, you know?

BM: Right, right.

DT: And, when I came back into the fold with him, I was just like, this guy is a revolutionary because he’s so positive and genuine. And just open to sharing ideas and opportunities. And up until that point, I’d never experienced that in fashion, you know, people were really guarded. Like, I always said, early on, this guy’s ushering in a new era of the nice guy.

BM: Yeah, I remember you saying that in another interview.

DT: It’s just true, man, to me anyway, you know. So, I try to maintain and it’s not easy to do. Like, he had a unique ability to inspire people through encouraging them in a really great way. And just being open source. I think that’s currently the thing that I am trying to really tap into, especially in audio where, like you said, I think in the audio industry, I’m an outsider in a similar way that he was an outsider. I think one of the genius things that he did was figure out how to access a new market and then not just try to surpass all the people that inspired you to get to where you were but bring them with you and educate this new consumer base about who those people are. And so in the show at Lisson, for example, every thing that we built for the show that, you know, that I built, cause everything in that show is more unique and handmade than anything else that I do. I knew because of the context that people are gonna be like, is this art? What is this? Cuz I get asked that every day, what is this? What are we doing here? So I wanted to approach that whole system the same way any artist would approach sculpture making. Just so that at the very least my response to that question is like, I don’t see a difference between the way I produced this whole system and the way any of these other sculpture works were made that are out in the rest of the gallery. But you know, each of those individual components, I’ve made an extra effort, to like, if I want to make something, for example, the amplifier, the power amps that I made, there’s a single 300 B amplifier. It uses like a, a very common circuit topology. It uses a driver tube and in cascade driving the grid of the 300 B, it’s a very common way of building, like the most iconic kind of single ended triode amplifier. And it was important for me to tell the story of who inspired me to build this kind of amplifier. So I explicitly made it into a collaboration and based the circuit on a circuit design by one of my, sort of like heroes from within that underground audio world and, you know, as much as possible. I tell the story of Herb Reichert and why he’s so inspirational to me. And I feel like that’s Virgil, coming in my work, you know, of like his first little LV activation, you know, that being produced by Rob and making it into kind of like, LV as Alife 99, you know, like he didn’t have to do that. He could have even hired Rob to produce something for him and not told anybody about it, but that wasn’t his way. So as much as possible, I try to also. Man I channel him so often just like, “What would Virgil do in this situation?” Socially, professionally, creatively, but those are all ways that I think, and this is something that I learned from V.

BM: Yeah. I see that completely. I never met Virgil, but I grew up in San Diego and it’s crazy to think about how there’s so many people I know, just in San Diego who personally worked with, or were given opportunities by Virgil and they’re still getting help through him today. Like, there’s a guy I know who I skated with growing up with got boxes of shoes from Off-White, you know? Just cause Virgil saw him on Instagram one day and liked this style and tricks, you know?

DT: I mean, that’s another thing is when I met Virgil, I had kind of just gotten on Instagram and I just used it to share whatever, just like my friends, but he already had a huge presence on Instagram. And I remember he asked me, I was like “I don’t have much of a presence on Instagram, I don’t really do much.” And he’s like, “Yeah. Is that intentional?” And I was like, not really, like, I just don’t know how that works. I don’t know how to do that. And it’s incredible when that thing starts to happen and you start to of leverage it. I work with a lot of people I’ve met through Instagram and I know that that was also something that he did all the time is like, you know, somebody sent me something, it looked dope. And I have a bunch of people that I have really important working relationships with that it was just like homie posted something, tagged me. And I was like, oh shit. Like I need that. I need that in my mix.

BM: What’s what’s your perspective on formal education? Um, cause you dropped outta high school, right?

DT: I dropped outta high school and I dropped outta college.

BM: Oh shit. Ha-ha. I did not know that.

DT: When I was in high school, I basically began to have a problem with the kind of authority within my school, after my junior year of high school. And I could just tell, like, it wasn’t gonna be an easy year. My senior year, I had a kind of running beef with the principal of the school. And I could just tell he was gonna try and make my life difficult. And my dad was just like, fuck it. Why bother, you know, like, what do you gain by going to high school for one more year? He wasn’t like just like drop outta high school and be a bum and do nothing, but he was like, drop outta high school, get your GED and just start going to college. I think even he was like, college is so important because like, my dad is also my my dad, but I think he has a really similar perspective as me on formal education. But you know, I’d say formal education or not, it’s important to always be studying, studying is super important and researching is super important. You know, for me anyway, the way I work, I think one of my strongest assets is that I have this like endless hunger to learn stuff. And that can be obsessive, right? Like with a single ended amp design, or like stuff that I learned. So anyway, I dropped outta high school. I got my GED and I went to a trade school to learn audio engineering. I did learn a lot in that school about the science of sound. And the one thing I did complete was an associate’s degree, at a technical trade school, basically. Most of the people that complete a program like that will go on to be an assistant engineer in a music studio. So I finished that, but it wasn’t really a goal of mine. It was just like, that was just two years of college. And then I moved into the city and I enrolled in the new school at a continuing education program. It’s like a bachelor’s program for people who haven’t fallen into a traditional school route. I started Nom de Guerre while I was still in that program at the new school. And then I just went into a very minimum, idle college mode where I was like, “I’ll eventually finish.” But I have to work, like work. Like I have these opportunities that are too valuable to not pursue. I started Nom de Guerre, I think I did like a year of Nom de Guerre taking a few credits at a time and I had one professor who was a super inspirational guy to me. He’s an artist. He taught like a contemporary art analysis class, or sort of a contemporary art theory class. And he was just like an unofficial advisor. At least I felt like he was an unofficial advisor to me. By that point, I was able to take his class like multiple times, you could just take the class over and over and over again, and I’d been in this class for like, I don’t know, probably 18 months or something. And he just kind of took me aside and was like, “You should just do what you’re doing.” Like you can keep going to school at any point, but he’s a New York guy as well. So he’s like “If I could go back in time and just do community more than school. That’s a trade off that I wish I’d made. You should just go and do that. And this will always be here for you if you wanna come back to it.” I think knowing full well that I wouldn’t, but yeah, so I never finished, I never finished a bachelor’s degree either, so I’m like a professional education dropout.

BM: So mostly self-taught?

DT: Mostly self-taught. You know, the kind of audio that I do now, there’s a lot of foundational stuff, like I said, that I learned in school, but you don’t really learn the kind of audio that I’m attracted to. Its really sort of like an underground community, and it’s a culture that things are generally handed down, especially these days, like I don’t know of a school that you could study tube electronics. You have to have that obsessive research thing. And Virgil had that. Virgil knew because he was still a student when we were the same age, but he’s like one year younger than me. But because I started Nom De Guerre when I was 23 years old and I was doing Ojas, like I was out in the world as a creative and I was like 21 or 22. So he knew stuff about my career that I couldn’t remember, you know? So he had that like, you know, at 2:00 AM, he’s going deeper and deeper in some rabbit hole of some cultural musical creative thing. And I think a lot of people are just born with that.

BM: I’ve been thinking about going to grad school myself, so I’m definitely picking up game right now.

DT: I always wanted to. The cool thing about grad school is that it’s kind of the one part of your career in academics that is just like, “I’m gonna take a few years and just go super deep on something.” Higher education becomes more and more of that, where it becomes more and more specific and personal. Whereas you know, high school is the opposite of that. I mean, it’s important for sure. You know, you need to learn how to do math and you need to learn about physics and science. But it’s very broad.

BM: I know Virgil would talk often about how his degree in architecture was his most valuable asset in pretty much everything he did. So that’s something I think about a lot for sure.

DT: Again, everyone’s path is their own, you know, like I always try not to be like, “I know the best way to do it.”

BM: Do you prefer more strategy and planning versus just trusting the process and being more spontaneous?

DT: I’m really bad at planning. I’m just kind of a go with flow kind of person. You cannot control anything in life. And I really try to obviously identify which opportunities seem like the best and go with them. But yeah I’m definitely not like “it’s gotta be this way and only this way.” You know, I have no strategy for what I’m doing in my career at this point. I’ve done literally, no paid marketing, advertising, brand positioning. I think for me, it’s like positioning is just who you’re with. You know, if you identify the people who inspire you and you can immerse yourself with them, then you don’t have to contrive opportunities. They’ll just naturally happen, you know? And I think another thing is, at any point I could be like, “Oh, there’s other people that I want to align myself with,” but if you’re not aligned with them, for one reason or another, you’re just not and you can’t force those things. Like if you start talking to someone about your work and they’re not interested in it, you can’t force that. And I think you also have to appreciate when someone’s enthusiastic about what you’re doing. It might not be your hero, but you have to appreciate the fact that that person’s enthusiastic about your work and if you can align with them and build something of value together, you gotta take advantage of those opportunities. Go with the flow, its a good strategy.

BM: Beautifully said. Definitely leads to more fulfillment, I’d say.

DT: Certainly. Yeah, hopefully. But you can get very frustrated trying to control everything. And the fact of the matter is that you can’t control anything.

BM: Right, right. Before we end, I did want to share a few things with you real quick.

DT: Please.

BM: So like, while I was preparing for this interview, just doing research and stuff, I was listening to, “Always Returning” by Brian Eno.

DT: Which album is that on?

BM: Its on Apollo.

DT: Okay.

BM: So I was listening to that and I just happened to be on Virgil’s Instagram page scrolling and I don’t know, just listening to that song, scrolling through Virgil’s page, there was like this crazy feeling of sadness, but like a overwhelming beauty, you know?

DT: I love that.

BM: It’s cool to just think, the title is “Always Returning” and you know, Virgil’s gone, but still here, you know what I mean? And that experience, I’d suggest just listening to it again with that in mind.

DT: I’ll do exactly that. I mean, I have so many conversations with him in WhatsApp and iMessage that its just crazy how you can relive an entire friendship nowadays through all of your written and visual communication. And I don’t spend a lot of time on his Instagram, but I wonder how it works.

BM: He knew what he was doing.

DT: Yeah, his Instagram is so important. It’s a super important time capsule, and in a lot of ways is like, his greatest book, you know?

BM: I agree. I agree. That’s pretty much how he described it, I think. I don’t know the exact quote, but like, just documenting everything in real time, more than anyone.

DT: I remember the first time we spoke, he told me how he’s obsessed with the evolution of streetwear and that he wanted to write the book.

He wanted to be the one who wrote the book on it, and I think he did.