instagram.com/carolinecalloway, Played by Caroline Calloway

Written by Martha Fearnley

There is a famous quote that gets flung around a lot when we try to write about writing. It is the opening line to Joan Didion’s essay White Album, an essay that is largely a treatise to self-mythology and its pitfalls: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” The need to self -mythologize is an easy one to recognize in ourselves, which is probably why this quote gets flung around so much. Confirmation bias, pattern-recognition, even belief in a higher power are all versions of the human need to wrestle difficulty, suffering, and achievement into a tidy narrative arc. In doing so we might locate ourselves amidst the chaos.

In 2010, the iPhone with a front facing camera was released. Instagram came into being in 2012. We suddenly had new methods and means by which to share ourselves, to tell stories about ourselves, and more importantly, to each other. The locus of our self understanding was quickly externalized and marketed, and the medium itself has become not so much a record of one’s life, but its presentation; one that could make it a suitable window display for a rotation of products. This paradigm is what makes the Instagram presence of influencer and writer Caroline Calloway so compelling. Her content contains the same sense of raw, earnest curiosity that we used to have as a generation raised on the internet, one which has since been overtaken by cynicism towards social media. There was once a brief period when the idea of laterally sharing thoughts and information was exciting, when the prospect of being intimately connected regardless of space and time was fun and not, as it has proven to be, psychologically exhausting.

Caroline Calloway as an influencer is perpetually engaged in an act of self mythologizing That most of us relegated from Instagram to the Notes app long ago. Her posts are a meticulous record of her young adult life from the beginning of her account in 2013 to now, chronicling ages 21-29. She doesn’t discriminate between tragedy and success — almost everything makes it to her Instagram at some point or another, in a form of memoir that is both calculated meting out of information and bursts of extremely personal divulgence. She is not the only influencer to utilize exposure in her online presence, but few others do with the same idealism. In a recent post, Calloway wrote, “My social media is my art. It’s not my only art form, but it’s a major way that I process and create my experiences in the world. I’m allowed to center MY feelings and MY experiences in MY art. If you don’t like the free content I create on here—if you don’t consider it art—leave.”

The defensive tone of this particular caption is not unwarranted; Calloway’s writing has drawn more public ire than appreciation. Influencers, especially female ones, generally do not use their platforms for the express purpose of elevating the act of living their lives into ‘artwork’. Mysteriousness is preferred over divulgence, coolness over earnestness. Calloway’s persona is neither of these things. Yet, as Calloway herself understands, nobody watches a performance for its elusiveness; nobody reads anything for its sense of ironic distance.

Like many, I first became aware of Calloway through Natalie Beach’s essay, I Was Caroline Calloway, published in ‘The Cut’ in September of 2019. The essay details the years that Beach spent being friend, assistant, ghost writer, and side-fiddle to Calloway after meeting her in a personal essay class at NYU, ending after a particularly hellish night in Amsterdam. It is ostensibly a story of two girls’ creative codependence, yet the work’s gravitational pull is Calloway’s chaotic allure. Beach admits this pull herself early on in the essay, “To my other friends, I described her as someone you couldn’t count on to remember a birthday but the one I’d call if I needed a black-market kidney. What I meant was that she was someone to write about, and that was what I wanted most of all.” In Calloway’s response essay, written a year later, (a characteristic of her oeuvre is that she is helpless but to respond to every piece written about her), she talks about the impulse to write herself: “I don’t know what, as a child, made me believe that being a famous memoirist was going to solve all my problems since all anyone ever told me was to pick a different goal. But I latched onto a vision of myself in a ball gown, with flowers in my hair, inside a castle, inside a story, inside a true story. I wanted that.” When Calloway manages to cut out the middle man of her own interpretation, Beach finds herself devoid of a muse, of a life to mine for her own literary purposes, and she is forced to come to terms with the consequences of feeding such an unbalanced friendship. Beach writes, “I had built my whole career around my commitment to her persona — crafting it, caring for it, and trying my hardest to copy it… (b)ut in Cambridge I didn’t see someone I wanted to be but a girl living with one fork, no friends, and multiple copies of Prozac Nation. Now I saw Caroline for what she was — a person in need of help that I didn’t know how to give.”

In the intervening time between the end of Beach’s essay and now, Caroline has continued to use Instagram as her primary platform. Her profile is a manifestation of this life-inside-a-story, the images themselves a collection of thematic objects chosen and developed over time. Experienced post by post, Calloway’s Instagram is unstructured and earnest, her captions read as diaristic, impulsive, verging on the melodramatic; experienced in its totality, it is a deft understanding of herself as a protagonist. She repeatedly charts the arc that brought her to her current infamy, laced with mistakes and public upsets, but never devoid of romance and relatable fallibility. We move from the starry-eyed NYU student with a dream to go to Cambridge, to Caroline at Cambridge, going to balls until dawn and studying in dusty libraries. Then we move to Caroline the addict, her childhood with a mentally ill parent in less privileged circumstances. After that it’s Caroline in New York, going to therapy and pilates, wearing flowers in her hair and painting on her floor. We get the pitfall stories, the ones that made her infamous, like the time that she set up an ill advised ‘creative workshop’ near the height of her influence and accidentally ordered enough Mason Jars to stock a small factory to her studio apartment. The stories serve as self-sustaining entities that build a body of work which is — criticisms of form and craft aside — a unique exercise in memoir that, to my knowledge, no other influencer has been able to create.

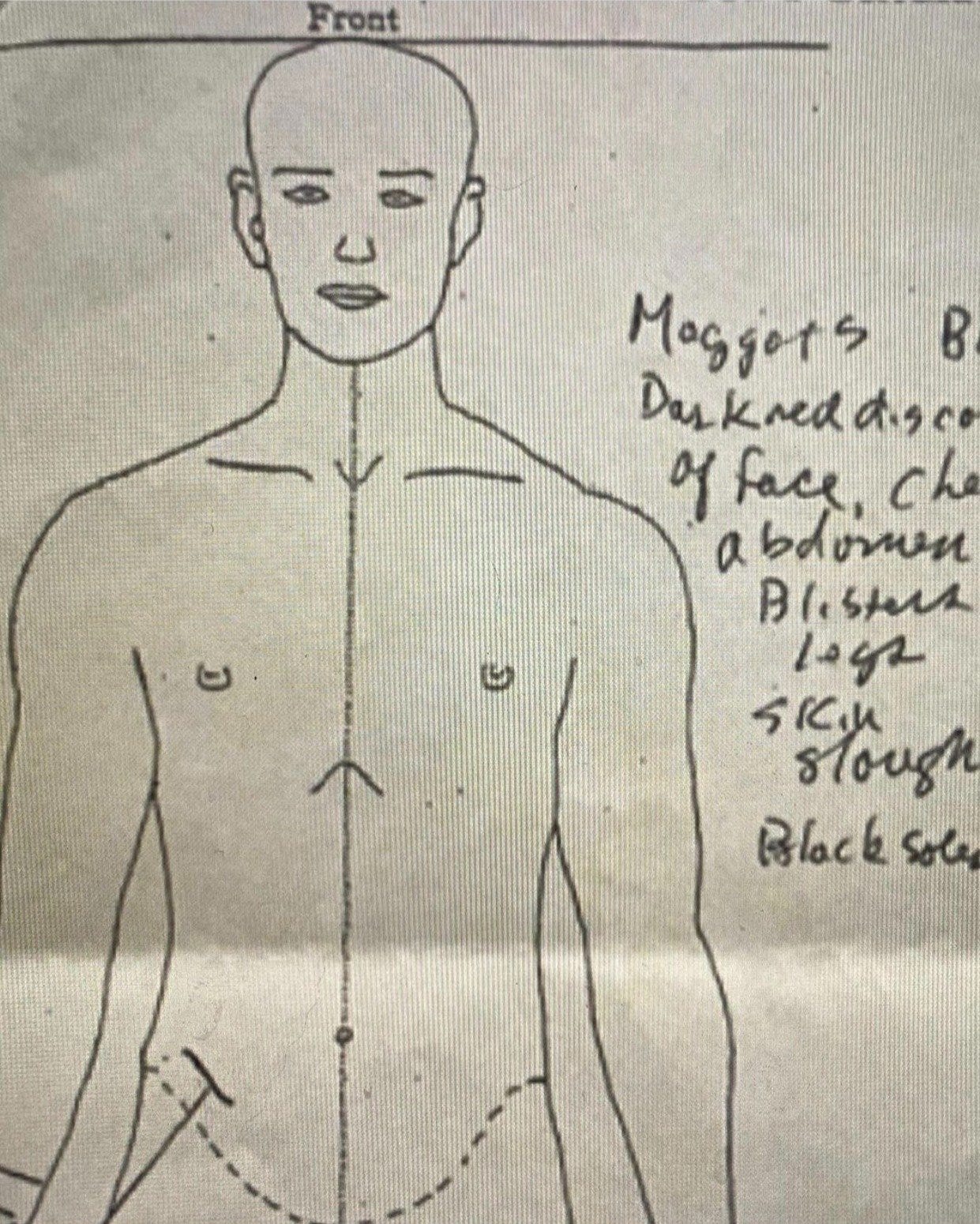

What Calloway has done moves outside of traditional memoir in its intimacy, as well as its visual acuity. Through Instagram, she has created a shorthand for all these stories, no doubt an instinct gleaned from her years studying art history (which is itself another pin in the Calloway signifier yarn map). Her grid has little variation: the color turquoise, flower crowns, photos of dawns and sunsets from inside her apartment, Matisse’s Blue Nude. Each stand in place for gradations of feeling or powerful memories which are usually detailed in the caption. They are punctuated by retrospectives and intertwining of previous thematics, along with personal details about her own life that run the full gamut from raw to coy disclosures; from posting her father’s autopsy results to placing butterfly emojis over the faces of ‘lovers’.

To go beyond Calloway’s Instagram and speak to the little writing she has (self) published, it is unsurprising that Instagram remains her primary medium. All of her formal writing shares a disinterest in speaking for itself, instead it is just another vehicle for Calloway’s self projection, but slightly less convenient. This is not to say the writing is bad -- Calloway’s work has strong echoes of Wurtzel in its immediacy and introspection -- it just lacks the patience needed for traditional form. In reaction to Beach’s I Was Caroline Calloway, Caroline wrote her own essay: I Am Caroline Calloway. The essay is unabashedly impatient and scattered; it pores over details and discrepancies that are largely uninteresting to anyone apart from Calloway herself. As Calloway points out in the essay, what Beach lacks in insight she makes up for in rigor, and vice versa with her own writing. She also writes about her particular dilettantism in the context of her studies at Cambridge, describing the art history damsel with a love for close-reading and the storybook world of old money academia who could never turn an essay in on time. At the same time, to focus too much on form would be to miss Calloway’s quiet, sophisticated turns of metaphor, her emotional fluency, her often withering self awareness. This purposeful unfolding of one person’s emotional core is what makes Caroline Calloway the person, as is the case with all memoir writing, compelling. A lack of rigor also means her writing is not diversionary, not obscure.

To write the self is to take measures against damage. The cliché of the artist’s compulsion to create is that it is done in order to evade death, to live on posthumously. I think the instinct is less grand. Creating stories about oneself is a quotidian protective exercise, like buckling a seatbelt. Whether the stories are cruel or self aggrandizing, they are protective against more pollutive interpretations, against other’s decisions on how much we matter and where we fit. This is, to an extent, also the function of social media: an attempt to control the narrative.

As an influencer, Caroline Calloway’s diligent logging of herself through her own eyes feels, in contrast to most influencer’s accounts, like it isn’t actually for us. Her Instagram is not a more perfect reflection for an anonymous or imagined ideal audience, but the work of an artist who has found that her voice and imagination magically fit a medium. One would think, looking at Calloway’s Instagram and her writing, that this woman’s instinct for self protection is non-existent. She writes about things so personal — in one memorable post she takes us on a tour of the house in which her father completed suicide; the house has not been touched since — with such an unstudied and vulnerable voice, that she must have some penchant for masochism.

Despite this, a sense of joy is woven throughout, a Sagittarian optimism that allows Calloway to crest buoyantly through and over her worst moments, like any good heroine is required to do. The confounding element of Calloway is the unanswerable question of whether or not someone ‘deserves’ something when it has not been ‘properly’ given, whether that is fame, or the right to call oneself an artist. Calloway’s work violates the social agreement of Instagram as a space where we are supposed to perform. This is what makes her Instagram and her online persona a magnet for vitriol and fascination. Despite cries that all this documentation is the end of privacy, few of us truly use it to share ourselves.

The prospect of granting permission to oneself is intimidating, and often we are angered by anyone who acts without it, especially in a world where centralized institutions of media have become less esteemed and less necessary. In this moment when we are all immortalizing ourselves on such tenuous and fluid grounds, we are stuck feeling at once anonymous and overexposed, shouting into a void for not much more than short-lived gratification. What Calloway does is embrace this space of overexposure; she is idealistic and generous in a way not many of us are prepared to be, and in the end, that makes for good reading.

To learn more about "it girls" past and present, check out the podcast It Girl Theory, co-hosted by Martha Fearnley.