FCKKDD Up: A Conversation with Raafae Ghory

Written by Maya Kotomori

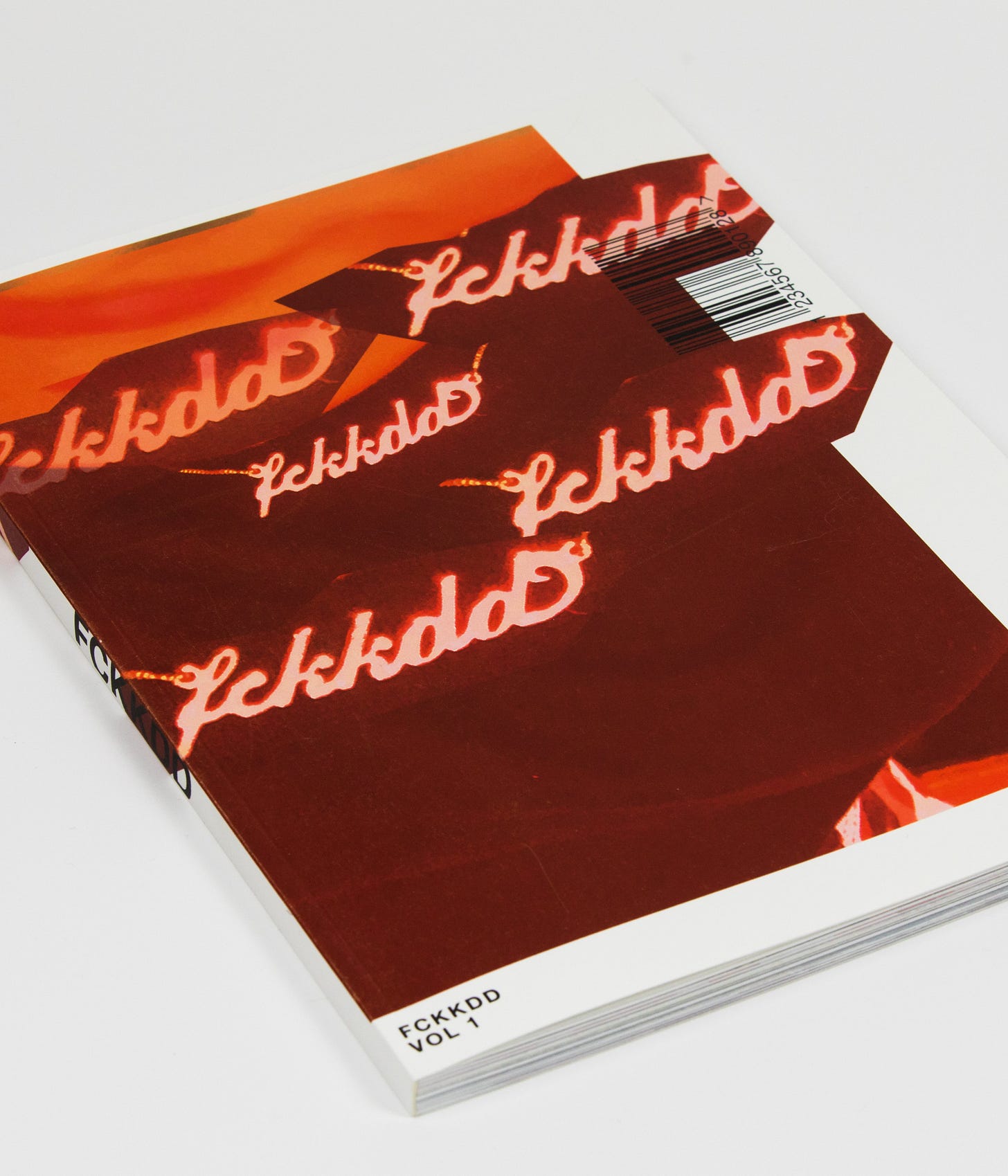

The laptop rang on a Tuesday night. Dehydrated, STP's Maya Kotomori pinged artist and friend Raafae Ghory into the Zoom call, eager to quench her thirst with some good art-chat. Raafae Ghory (b. 1997, Lahore) is a photography based artist whose recent work explores the ways in which a persona can be performatively generated, dispersed, and then corrupted in and across digital and physical spaces. We chat about it all in the wake of his sold out book, 'FCKKDD.'

Maya Kotomori: What was the process of making this book like?

Raafae Ghory: It’s funny to think about an artistic process when memes [are the] subject matter. That's so silly! Archiving these images was something I did naturally. I didn't think about it as a process or practice until I had the idea of making a book. Then I started going back through the images, re-experiencing them. I came across some really good texts that became the foundational theoretical framework of the ideas behind what I did.

MK: What did you read?

RG: The first one that put me in a good place was Giving An Account of Oneself by Judith Butler. After that, I read The Undercommons by Fred Moten, I would recommend that if you haven't read it. I read The Fisherwoman by Toni Morrison, also.

MK: Fire, I love her.

RG: Have you read that piece?

MK: YES!!

RG: Yes! And also, The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord, which I just posted on my story yesterday, ‘cause I was thinking about Debord, and some French Marxists too.

MK: So, the book is a processed version of your trap account on Insta that became a book! Beyond the account, where did you see that materiality going?

RG: I took the content of the account and wanted to recontextualize it into the form of a book. We're so used to seeing these types of images right in front of our faces - on a screen - all day. Outside of that, [the book] is a way of reading the world around you. It's subject matter that lives online! That’s so ingrained in our heads that we often don't take the time to think about what we're sharing or consuming.

MK: There was a lot of personality within 'FCKKDD.' There's also a lot of homies in the book. How did they feel to have that shout out in print?

RG: I don't really know! A bunch of friends have seen the book in its earliest form when I made it three years ago. When I show it to them now, I get a lot of smiles. I think the content and just the nature of the book are both so overwhelming that people don't even like when they see themselves in it, and they're still processing all of the material in between that you have to go through, like on an online feed.

MK: If you could define that material in between, what is one word that you would use to define it?

RG: Ether.

MK: Ether - I love it. Did you know that not only is "ether" an imaginary space, but also a chemical? They used to use it back in the day as an anesthetic. I'm not super familiar with its structure, but I know it's really bad for you.

RG: Well, there you go.

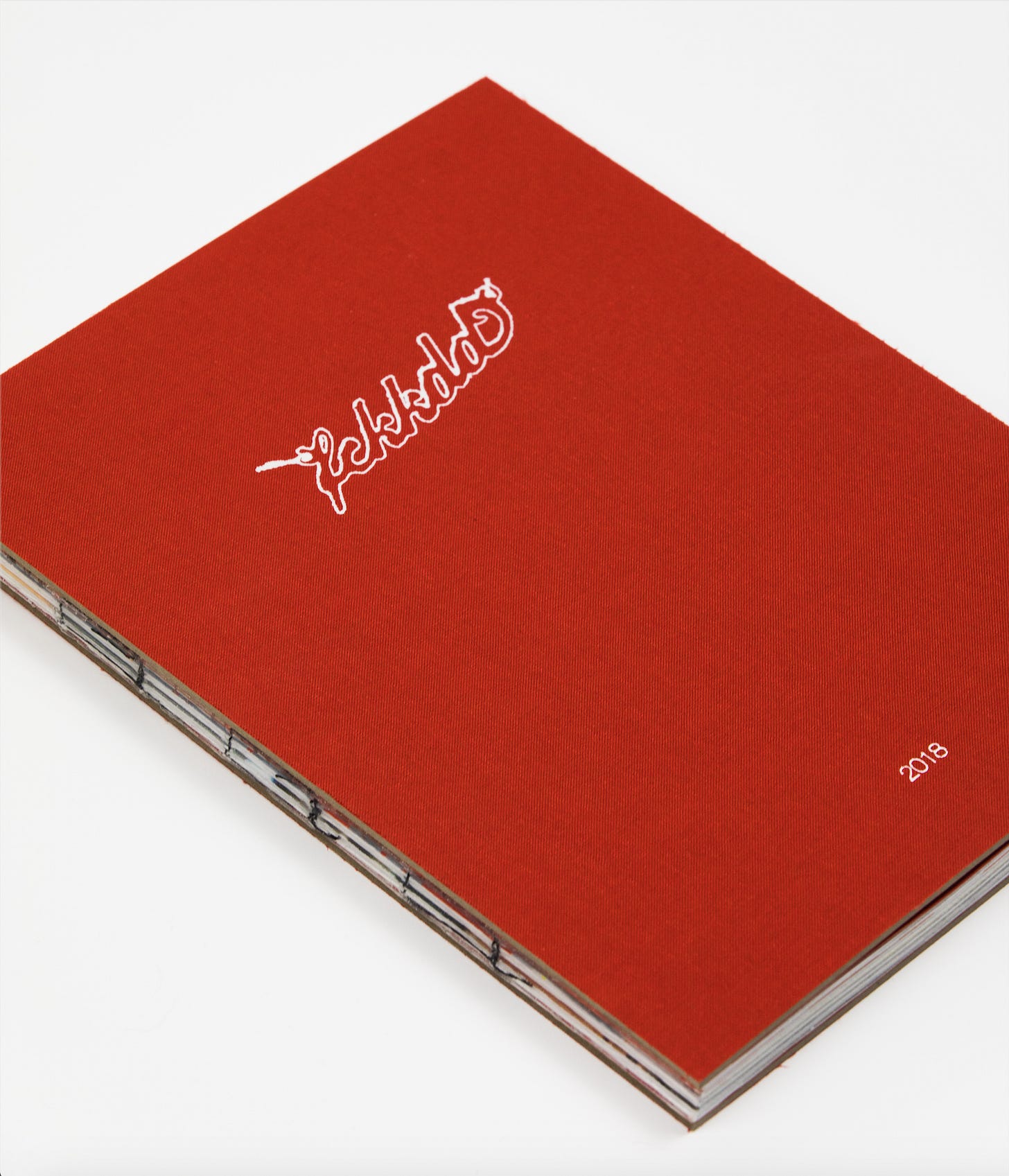

MK: The book feels like a really broken down time capsule for 2018. Why did you pick that year specifically?

RG: That's a good question. I feel like the pain [of that year] was definitely an aspect to that. I also just happened to be in a class where I had free reign on what I wanted to create. I was trying to figure out a way to organize ‘FCKKDD’ in a way that made sense, and I also wanted to have a hard start and stop to the work. If there wasn't that start and stop, the work becomes just like our feeds - it just keeps on going. Having a "year" was a good way to contain that set of work.

MK: Do you hope to make more collections? The side of the book says ‘Volume One’ and I'm trying to try to see another one...

RG: That's kind of my intention. I mean, as you know, I still keep this 'FCKKDD' archive online and it's an ongoing thing that I'll do whenever I feel like it. I think the next one that I would do would be for the year 2020. It’s kind of obvious because we basically lived that entire year mediated through our technological tools, and most of our social interactions took place through the Internet. I want to look back at that, but I'm not really in a rush. I don't really want to process that that year so soon.

MK: When you said 2020, it made me think back to Society of the Spectacle and the idea of the information highway, and the Agora, and how Debord made those connections with public space as a digital experience. With wanting a hard beginning and a hard stop, how would that translate into the layering that you used in the book? What are your opinions on time in that way?

RG: I did the layering and the collaging in the book as an aesthetic way to capture what it feels like to be in the internet. The “higher ups” have said Instagram is all clean lines and grids and you know, infinitely scrolling timelines, but it doesn't feel that way for the most part. It can just feel like a disorganized sort of overstimulating experience of information, that's never ending. I wanted to mimic that feeling.

MK: Logic question: is this the first physical book you've ever made in print?

RG: This is the first one that I'm putting out to the public. I made another book in 2017, that was just my photographs of my friends, and another for my project about Mecca. Books are my professional career right now. I work at a book publisher called Conveyor Studio in Jersey. It’s a cool spot, there’s only four of us in the shop. They have their own publishing label, and they do a lot of just on demand printing for museums and places like that.

MK: Bookbinding is fascinating!

RG: It is! All 2020 I was still consuming content online, and that was what I posted during that time on my private account. That [reminds me of] one of the main questions that I posed for myself when I was making the book: how can you negotiate a personal experience against the idea of a collective consciousness, how might a stranger who doesn't even know me be able to relate to the images based on content and subject matter? That [relationship] is ubiquitous, but then again, at the same time, it's definitely a piece specific to it’s time.

MK: A lot of other artists right now put out self-defining work that is all identity politics, and you don’t do that at all, while building that relationship with the audience. It comes out in a lot of your other work too! I was going through my story archives earlier, and I remember when you had ‘Hajji’ at the Tisch windows for all of January and February and March…

RG: And April ;)

MK: This man said we got a four month run! How do you relate yourself in terms of those two projects - ‘Haajji’ and ‘FCKKDD’?

RG: That's actually something I've been thinking about a lot lately and most of my traditional photography work revolves around these two words: like social documentary in a sense. At the same time, I was thinking about documentary as a form and what exactly that means. Even though it (FCKKDD) doesn't really have the defining features of what one might consider a documentary, it's still very much an object, an artifact of smaller artifacts that connect to different people in society.

MK: Super leading question but: how do you feel about the Internet? It’s funny how the internet was started, you know, as this big democratic network, and now, Trump is banned on Twitter? How do you see that [shift]?

RG: That's something I think about almost every day when I'm at work. I guess it's really just a big double-edged sword in a sense, because I, myself, when making this book, I wrote a 15 page paper about how memes are the single most democratic form of social critique that we have to this day. But then again, at the same time, the Internet has enabled a space of unparalleled consumerism and just enabled this sort of obliviousness, if you're not careful. Then you have all the other stuff that goes along with it, like the rise of the far right and that weird space.

MK: Yeah, because the Internet facilitates everyone, it facilitates everyone. And it (internet) also isn't a neutral thing either. The internet can fit certain agendas which is probably my favorite aspect of the book. The object itself is that the one thing that unifies it.

RG: Another question that I was asking myself was how does our relationship with these images and cultural obsessions change with time? Because there's a lot in that book that now exists as a dated cultural object in a sense, because we don't share those images. I was asking the question of what happens to these images that we move on from? I was scrolling on Twitter and there's people talking about ancient memes, which just popped up today. Like the original Wojack faces, you know what I'm talking about? Just out of nowhere, those are coming back up after what, 10 years of meme progression?

MK: That says a lot about the importance of the archive, because something really old can take on a new meaning, where the old thing is extra-important because it's really old. And now the Internet is speeding that up where even the book feels distinctly "2018" though 2018 was only three years ago.

RG: Yeah. It's insane. It's crazy.

MK: What is your favorite ancient meme and how did you feel about Pepe the frog censorship?

RG: I don't even know if I have an opinion on that. With memes, how can a certain group of people hijack an image, you know? [Pepe] has been recontextualized so many times on 4chan and Reddit. I don't know if you're active on Discord, but some of the Discord groups I’m in all use Pepe. The second you look at it, it just brings up these associations that have kind of been ascribed to it, when at the end of the day, it's a picture of a frog. It's so weird how a seemingly meaningless image can hold such cultural weight.

MK: The power of the zeitgeist, and also the power of concealing something is exactly what ‘FCKKDD’ subverts. It also has a dual existence. It still is a private account, and it is a [sold-out] book. Before you opened the book to the public, did anyone random who doesn’t follow the account see it?

RG: Yeah, actually. It’s a funny story. I brought the book to Dashwood about a [couple months] ago, and I was showing it to Miwa. She was really into it, but they're not taking in books right now. While I was showing it to her, this random man in the store just came up and entered the conversation. And he was like, “Oh, I'm actually working on a project about the Internet, your book seems like it's right up that alley.” So I was like, “Yeah sure, you want to look at it?” And he was like “Sick, how much? I'll buy it right now.” And then I sold it to him at Dashwood.

MK: So you subverted Dashwood at Dashwood.

RG: Yeah, exactly. I was like, “you got Cash App?” And that random person, I think his name is Dylan or something, got a copy of the book before I released it.

MK: Do you have a favorite style moment or time period?

RG: Kiko Kostadinov, or Old Navy.

MK: Bro, Old Navy is the shit. I remember like three years ago everyone was trying to bring Gap back and I'm just like, nah nah nah. It's all about $5 tees at Old Navy.

RG: When I was a kid my mom always used to get clothes for me from Old Navy. I used to hate it so much. And now I’m finding the sickest Old Navy objects on Depop and thrift stores. I was not with it back in the day.

MK: Should we be expecting any 'FCKKDD' clothing drops in the future or…?

RG: You know, maybe. It's not something I'm thinking about, but that might be cool. I don’t know what I would do, but nothing's off the table.

MK: “Weigh all the options, nothing's off the table.”