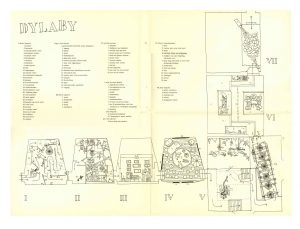

Dylaby, Stedelijk Museum, 1962

Dylaby, the dynamic labyrinth—a cross between a sunny kitchen, a haunted house, scaffolding, grandma’s attic, a ruin, and a sublimated birth trauma, which somehow forms a unit where people can grumpily or cheerfully lose their way.

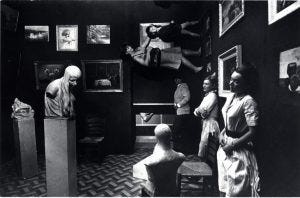

The participating artists—Tinguely with Niki de Saint Phalle, Daniel Spoerri, per Olof Ultvedt, and Robert Rauschenberg—cluttered the galleries with physical obstacles that required visitors to navigate raised platforms, climbing structures, and false stairways amidst a cacophony of noise. A celebratory atmosphere likely tempered any frustration generated by the deliberate lack of clarity in the exhibition layout, as visitors gleefully fired bb guns and danced in a sea of floating balloons.

Dylaby conjured both the time of childhood and a premodern era in which art spaces elicited ritual rites of participation and performance. Childhood was not just a metaphor in Dylaby: in the official publicity materials surrounding the exhibition, children were everywhere. They appear in installation photographs and in a documentary film shot in the galleries of Dylaby.

In engaging children within museums, as well as Sandberg’s specific aims for the Stedelijk, children served as natural instigators of participation and play in Dylaby. They invited viewers to shed their adult inhibitions and travel back in time to childhood, but also to a mythic time when art was not exclusively the province of the eye, but tied to a body in motion.

Most of the material on view was from secondhand stores or had simply been found in the street. When the exhibition closed, most of it landed in the garbage dump. “Dylaby” was, for those days, an extreme exhibition that tested the borders of art and activated the audience.