Drive-in Kill Spree - A Conversation with Eugene Kotlyarenko

“American Psycho for the digital age”... “TikTok Taxi Driver”... “not f*cking real”... “FAV MOVIE 2020”... “Aterrorizante, real e genial”... “based”... “fakebased and cringepilled.” Eugene Kotlyarenko’s 2020 film Spree has been called many things. It is destined to polarize—in both aesthetics and thematics, Spree is jarring. Drake produces it. James Ferraro scores it. Joe Keery stars in it. Mischa Barton dies in it.

While Spree takes place largely within a car, it is certainly not a Road Movie (travel as bildungsroman), neither is it particularly a “driver” movie (e.g. Drive, The Driver, Bullitt). Keery is the opposite of a suave, mute Ryan O’Neal or Ryan Gosling (the strong silent type, like Gary Cooper), and is less a Taxi Driver De Niro than King of Comedy De Niro with the eyes of Cape Fear De Niro. Vincent Gallo said that De Niro ruined a generation of male leads. “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by Robert De Niro’s mannerisms…” Keery's generation has been able to avoid this.

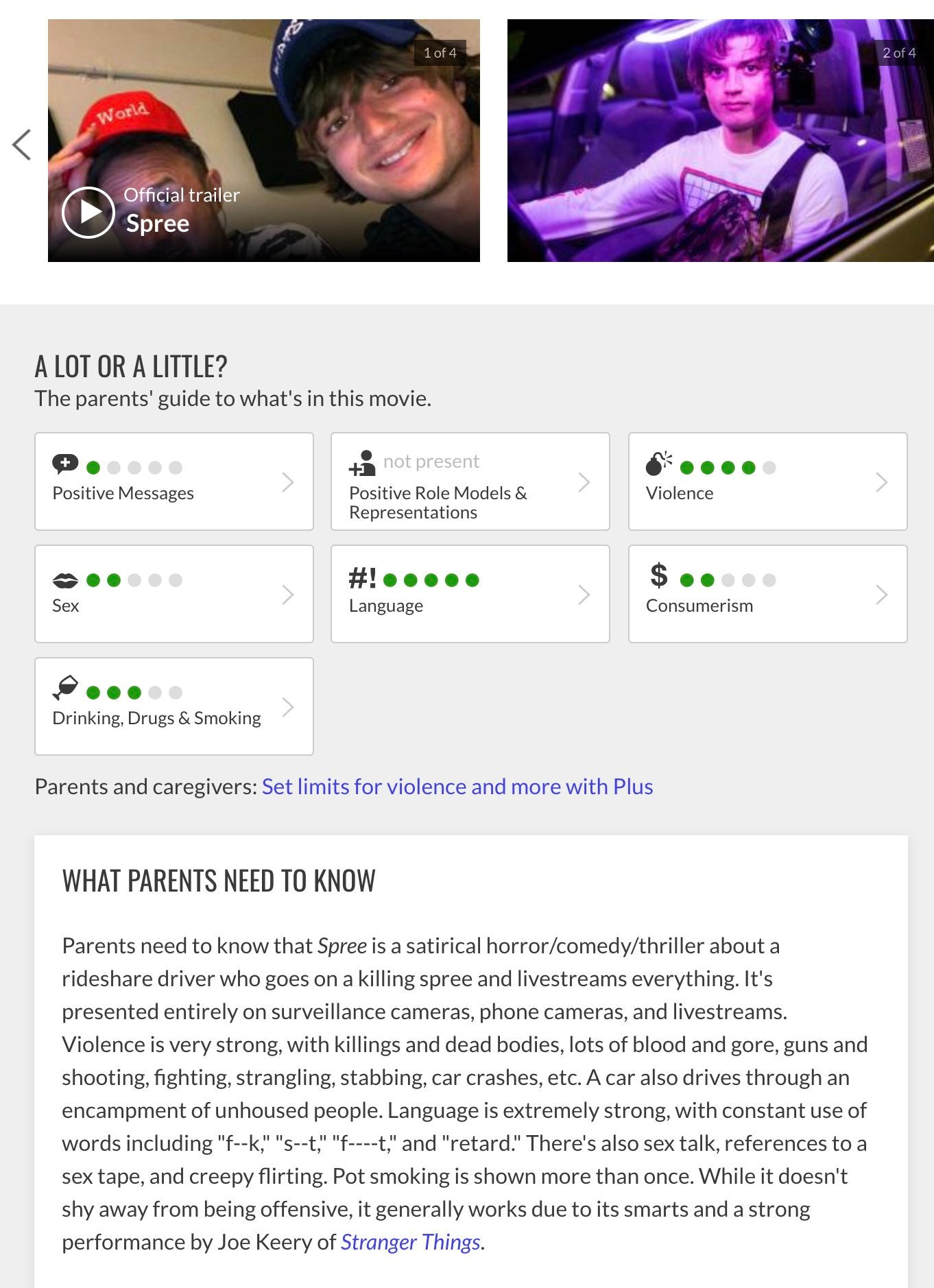

One of my favorite reviews, which director Eugene Kotlyarenko shared on Twitter, was that of Common Sense Media, which gave a succinct synopsis of plot and theme and allotted Spree one out of five stars for “positive messages.” The one positive message carried by Spree might just be to log off, and that's enough.

The film is not necessarily moralistic. Society has progressed beyond the need for platitudes about s*cial m*dia. If we can’t speak of it, we must be silent. No one can argue that Spree is not formally innovative, with its exclusive use of non-traditional cameras for narrative film. In the end, there is only one platitude that is truly apt for Spree: We truly do live in a society.

~

Anatole Alexander: Do you think the fact that Spree opened in the US in drive-in theaters changed its reception?

Eugene Kotlyarenko: It’s an added metaquality, given it’s a movie that takes place largely in a car. The film was shot exclusively on dash cams, iPhones, GoPros—so viewing it in a car creates a kind of 4D experience. People in England watched it in movie theatres, though. It’s also good to watch on a computer or a TV.

AA: Are you happy with Spree’s reception so far?

EK: Yeah, on one level I’m really happy because it’s the most exposure any of my films has gotten. There’s a really healthy discourse on Letterboxd. A lot of teenagers have seen it, and that’s the audience I wanted to speak to. On that level, the release has been a success. On another level, I don’t think it has penetrated any demographic besides cool teenagers.

AA: As in people who approached the movie primarily through knowing Joe Keery from Stranger Things?

EK: More so people who are just extremely online, but probably some middle ground between the extremely online and Joe's fans.

AA: Why was that the ideal audience?

EK: Because the film is most effective with them. They’re receptive to it. Like with any film I make, I want the maximum possible number of people to see it. I wouldn't be happy unless it’s the number one movie in America—I’m never satisfied after making a movie. I can’t enjoy the release unless it’s the most successful movie, but I've never experienced that feeling of being on top of the world after creating something. My goal as a filmmaker is to make an actual impact on the culture, and that happens after the film becomes a topic of conversation. Obviously, that’s different now, in 2020, with culture so broken up and bifurcated. You would have to do something insane to be at the center of culture, but it happens. Like Tenet is something most people know about.

AA: I read most of the reviews of Spree online and noticed some are exceedingly negative, almost like the critic had been wronged by the viewing of the film. Then there are some reviews that consider it super praiseworthy and novel. The negative ones, more often than not, moralize the film and judge it by certain unspoken ethical standards. What do you make of people calling Spree “nihilistic”?

EK: It’s been reviewed much more than my other movies, and those are mixed—some are negative and almost personal-seeming. The review that called it nihilistic was actually very positive. It was on Indiewire, and it was a really good review, about how Spree is campy and fun but lacked a moral imperative, so it was soulless or nihilistic. And that’s fine. All these critics are entitled to their opinions. To me, the movie is satirical, and they’re (the critics) trying to have it both ways. The way satire works is that it has to be brutal and savage, and probably has to have a philosophical perspective. People can extract morals or nihilism from it depending on how they react to the satire.

AA: Are the connections people make to Taxi Driver or King of Comedy helpful or do they obfuscate Spree’s novelty?

EK: On a marketing level, it’s helpful. There needs to be a hook, even if superficial, even if there are negative connotations. If you can get well known actors, they’re helpful shortcuts.

AA: Does Spree want to operate on an aesthetic level or is it supposed to be more socially impactful, political?

EK: I don't think you need to make a distinction. They can coexist. The movie is formally very radical; pushing forward experimental film language, and at the same time having a philosophical position. It critiques social norms that we take for granted, that we don't yet have the language to talk about. The mainstream reviewers who canned the film in the New York Times or the British press nailed it harshly because they're offended by someone saying that the place we’re in is fucked up. They think that it’s obvious, but they don't behave in that way.

AA: As in they don’t really process the thesis of the movie?

EK: They reject their complicity in the reality this movie depicts, and write it off with their own lies. They don't want to grapple with it; the attention economy, their existence as brand entities. That’s how they promote themselves. If they had to look at it really long and hard, they might have to deal with that. That’s how teenagers deal with it, they see all the pathetic scheming that every single person who exists extremely online has to go through everyday, and the actors are extremely attuned to that. The script was written with that in mind. To the critics, Spreeis the equivalent of social media = bad, because they want to boil it down to the surface level.

AA: Does Spree have any kind of fraternal relationship to Alex Lee Moyer’s 2019 film TFW No GF?

EK: Not really. The subjects there are explicitly fringe, whereas Spree is the embodiment of a universal feeling. It doesn’t actually represent a real type of person—only a generic mass murderer, as opposed to an incel or a troll. A troll is extremely aware of the subversive behavior they are engaging in, but a mass murderer is often emulating scripted activity, and unaware of the ways in which they play into a transparent, formulaic behavior. That’s what Kurt does. He puts together a social media formula, through tutorials, tips & tricks videos, life hack videos. Because he’s a hack. And the fact he’s murdering people is only a byproduct of sensationalism culture.

AA: Were you thinking about trolls at all when writing the movie?

EK: I wrote a movie about internet trolls a while ago, using them as the last bastion of being subversive and punk that are allowed to exist in a society where everything is commodified. If things are even just a little bit fringe, they’re gobbled up by Kanye or Rihanna’s creative team. Trolls are anti-everything and unable to be commodified—which was basically true until Trump came along and became the most highly commodified troll of all time. I agree with the assessment that subculture is dead, sold out, or at least very easily co-opted.

AA: Given that Kurt Kunkle’s [Keery] entire existence is predicated on being as visible as possible, how does Spreerelate to the opposite end of the spectrum, of being super anonymous?

EK: To be explicit, Spree is really a film about mass murderers as this post-Columbine phenomenon. These people don’t want to be anonymous, they want to be the center of the narrative, and they engage in mass violence because they’re deeply desperate to get there. I wanted to connect that with the participation in social media, with the prayers to get dopamine hits of likes, follows, subscriptions. Social media promises to put us at the center of the narrative. People who operate anonymously online have very different goals. In my movie, no one has private goals. Everyone is extremely surveilled and voluntarily participates in that observer-observed society.

AA: Kurt’s line about how ‘if you don't document yourself, you don't exist’ has been quoted frequently in reviews—do you think we’re trapped in this existential framework? Or is there anyway to go offline, to go back, without sacrificing your social life or ostensibly disappearing?

EK: Not really, considering existence within capitalism. I read that 52 percent of the world population is on social media, and taking into consideration countries where there isn't extensive internet infrastructure, that’s a huge number. That number means everyone is participating in the same economic model. The next wave of social media apps could change that a bit, though. Facebook is already irrelevant. Most of these apps were created by millennials, and it's possible no one will be using Instagram or Twitter in ten years. The next wave will be created by Zoomers who have a different relationship with this.

AA: They appreciate the wisdom of the “just log off bro” mantra more than their millennial counterparts.

EK: They have multiple accounts, often private, and are wary of what they put forward publicly. They go consciously offline a lot more than Boomers and Gen X, who still see these apps as “a way to talk to my family”. Zoomers just have a much more intentional relationship to social media, and might create less laissez-faire apps that are more responsible to our psychology and attention and exhaustion. Posters have such a conflict with going offline because it’s heretical. You can say you don’t need to exist in this framework, but then you're in purgatory.

AA: Has the reception of and your entire experience of creating Spree changed how the trajectory of your work as a director? Do you want to continue to make films like this, that confront similar issues?

EK: I’ll keep making satires. Satire is a hard thing for people who aren’t super cool or super smart to accept. Unless you get it and are willing to laugh, it will make you uncomfortable. I got the same response from my previous films, but it was less pronounced, because less people saw them. And those people who saw them were in the know. It was an audience who would accept your critique. Now, it’s much more open. There’s a long tradition of artistic satire, from Jonathan Swift to Paul Verhoeven to Brian de Palma. Even Hitchcock was a really strong satirist. When those films come out, people think they’re cruel or stupid or one-dimensional, and only later are people like, “Oh, that’s what that culture was like at that moment.” It’s an artistic representation of truth, and people weren't ready to accept on a naturalistic level.

AA: Are your films all a form of satire?

EK: Yes.

AA: Do you think that’s the best way to express these ideas?

EK: There are a lot of ways to do that. I also love melodrama, pure horror, physical comedy. The best works of art and literature and theatre and even music often have a really strong satirical approach, which I think some people don’t realize. Shakespeare is all satirical. Hitchcock is really funny. I consider Spree less in the lineage of Taxi Driver and more in that of Clockwork Orange, as something highly comedic and with a distinct moral framework.

AA: Does Spree have the strongest moral critique of all your movies thus far?

EK: It had to, because of its level of violence. My two relationship films are explicit indictments of hipster millennial culture, of “cool” culture, and are just exposeés on people who are so transparently desperate for validation and coolness. That’s what Spree is about, too. But some people don’t get the humor, and just think they’re “slice-of-life movies.”

Spree is available to stream on Amazon Prime.