Art in an Emergency: Guidelines for How Art Can Address Climate Change

When Olivia Laing first came out with Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency, I was ignorant to her tastes and the scope of her career. All I knew was that she set out to answer a question at the root of my thinking, what can art do? Due to her past as an environmental activist (and some misleading promotional blurbs), I had assumed that the question, what can art do, would extend forward into specificity- what can art do in a climate emergency? Laing didn’t do much for me, seemingly stuck in that iconic, overworked era à la Warhol, Basquiat and Haring. Funny Weather spoke of AIDs a lot, though, which I’ll return to.

For the artists out there who want to save the world, here is my primer on the potential of your impact and some notes of the kinds of work I think we need. You can scroll down to the first bolded point for the specific guide, but the following introduction is an explanation on why climate change is so difficult to address in the first place.

There is a difference between what is known in the mind and what is taken into the psyche and heart. Feelings are king, that’s who we serve. Though facts, information, and data represent reality, on their own they are not enough to make certain phenomena feel real. If we were different creatures, we would read the statistics on whatever matter, take them in and respond accordingly, but as Candis Callison points out in her book How Climate Change Comes to Matter: The Communal Life of Facts, climate change cannot “become real” to the individual without cultural mediation. For very few people, Al Gore running through a PowerPoint is enough to make climate change feel real. For most other people, it is not. Believing in climate change, thinking about it, feeling anxious about it, responding to it, and changing because of it- that takes work.

The difficulty of our environmental issues is that the reality of degradation is hardly felt. We encounter this reality through knowledge more than experience. How is it that every object I interact with is a poisonous one, gauged from a denuded and fracked earth and refined by various kinds of unjust labor? I’ve read about it. It makes sense that it is true. But it’s impossible to experience a global supply chain; commodities ricocheting like pinballs across borders. These things arrive to us innocent. We must think hard at the object in our hands to even glimmer the truth of it.

As an anthropologist, Callison understood that the “making real” of climate change is a culturally specific process. For the religious, a trusted messenger within the faith is necessary. For journalists, the scientist’s work complemented by confirming reporting experiences could be enough. For the indigenous people who Callison worked with in the Arctic, the messenger was undeniable. The cracking ice that had led to accidents while hunting was made all the more legible by a culture ready to listen to water. These examples are predicated on those who are paying attention or ready to “believe” in climate change. Attention is a labor not many of us have the luxury to take on. As Shklovsly notes in his essay “Art as Device,” “Held accountable for nothing, life fades into nothingness. Automatization eats away at things, at clothes, at furniture, at our wives and at our fear of war.” We let the evils of the world become familiar when they should be unfamiliar, wrong, unnatural, terrifying, dissociative, disgusting. Shklovsky’s opinion is that art is the device by which we laboriously resuscitate a world that has become overly familiar.

Callison’s work addressed that frustrating first step. The breaking of the news. This is what has been happening and this is what will happen. What kind of cultural work do we need to go beyond understanding, or acceptance? What kind of cultural work do we need to create a community ready to respond?

Ultimately, “climate change” is not a story we can really tell, as Kate Knibbs notes in her review of fiction, which tries to take on how the internet has changed our lives, “The internet is a place, not a plot.” (Though, I encourage you to experiment and try to make place into plot). The thing we can focus on, though, is how to be and how not to be. In a society fit to respond to the challenge of climate change, what do our villains and heroes look like? How can we prime the coming generations, and this one, for resistance, community strength, and agility? What kind of people survive without making the wrong kinds of sacrifices? What are the right kinds of sacrifices? I admit to being stupidly earnest. I don’t have many tactics for the truly cynical. Maybe one could channel their certainty into self-sacrifice.

I love you microbe. How fascinating, you are.

To again reference the likes of Bennet or Shklovsky, attention is animating. So, pay attention. Integrate an attention of the world into your art practice, and then give at least one person a new set of eyes. What is in your trash can, on the edge of entering the oxygen-less territory that will convert it from potential nutrient to sure methane? A component of leachate, that dangerous milk of inverted rot. What hormones live in the water? I would look at the work often shown at Art Laboratory Berlin for inspiration. It seems to be good fodder for the conceptual artist, especially.

Let’s be careful how our needs shape us.

My favorite line from Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler’s now appreciated cli-fi masterpiece, is “We must be very careful how our needs shape us now.” Butler is the rare individual to have converted the hyperobject of climate change into a story of a world that is difficult to live in. Violence and suffering strikes a people without the foundation for dealing with extreme resource stress on top of their usual social, economic, and political ills. How do we prepare people to draw together on impact instead of splitting apart? Butler helped show me how. One book series is not enough. There must be permeation of the lesson, a lesson which is necessarily in tandem with the education on ‘how to live lightly on the earth.’ How to become a resilient, agile, wise and kind people. Self-sufficiency and strength that is not isolationist or aggressive. It is through this strength that we might be able to create communities that don’t fear desperate strangers, but are capable enough to take them in.

It’s like when they made the cops into pigs.

Who are these villains? It is too easy to see businessmen as innocent. Imagining someone at a desk, making calls, delegating decisions down a pipeline of bureaucracies, doesn’t feel as dangerous as someone wielding a gun, even if we know that business has risked an innumerable amount of lives by betting on oil, logging, mining, etc. We must become creative in depicting him as the corpsefucker he is.

People often make the point that there is no point in naming and shaming someone out of their position. No matter who is fired or otherwise deposed of, someone will take the last villain’s place. We need to make it our job to make it unlivable to take such jobs. The position must become unattractive, even with the carrot of enormous profit. To do this, we must know their faces and their names. The greatest benefit of the elite is that no one knows their names. As Parish and Hansen point out in their essay about defining the category of ‘elite’, “Through the manipulation of cultural codes, the elite can all but vanish behind the screen of institutions and images that provide privacy and security and conceals the extent of their power, influence, and holdings.”

Do you know the 20 most carbon polluting firms in the world? Saudi Aramco, Chevron, Gazprom, Exxonmobil, National Iranian Oil, BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Pemex, Petróleos de Venezuela, PetroChina, Peabody Energy, ConocoPhillips, Abu Dhabi National Oil Co., Kuwait Petroleum Co, Iraq National Oil Co., Total SA, Sonatrach, BHP Biliton, and Petrobras. These firms are responsible for one third of the world’s carbon.

Do you know the names of the people behind them? Me neither. Here is an organization that will help you find them: Lil Sis.

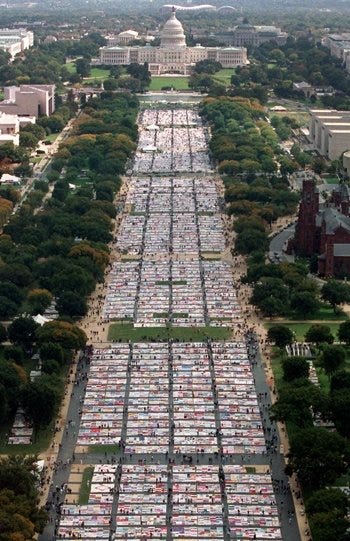

AIDs blanket.

The AIDs epidemic sparked an incredible fount of moving and effective protest art. It feels, at least from my view on history, to be the model of what art can do in an emergency. Olivia Laing focused on this work for good reason. Of course, she focused on particular celebrities within that effort even though the majority were made by ‘regular people,’ people like Duane Kearns, who was 22 when he was diagnosed with AIDs. Perhaps the reason he is smiling but squinting in that picture of him holding his AIDs blanket, is because of the sun. Alternatively, it’s also easy to see the saddest face in the world, arms spread, offering witness to his death sentence. This work, like all other protest art made during this period, wasn’t offered as a tribute to acceptance, but made in order to change shit. I don’t want to get into the gesture of weighing whether the work ‘worked,’ but imagine, for a moment, what the government’s response to AIDs would’ve been without the enourmous push to humanize the ‘gay cancer’. Imagine the anonymity of the historical record without it.

We can’t compare AIDs and climate change. However, let’s think about what makes AIDs protest art such an immediate portal for grief and rage.

Emmanuel Levinas, a philosopher and survivor of the Holocaust, has posited a somewhat simple ethical arguement. Each of us have a face which serves as a confirmation of our individual uniqueness on this Earth. When someone calls out to you for help and you see their face, you are bound to help. It is love we have to offer. “Love without concupiscence, in which man’s right assumes meaning; the right of the beloved, that is, the dignity of the unique.”

AIDs art revealed the pivotal truth: a lot of people died very quickly, in large part because of government neglect. That neglect was only possible because the sufferers largely came from an ‘undesirable’ community. The art served as a face for what would have otherwise been the faceless plight of the crowd. Look at Duane. Let’s refer to another iconic piece, ‘For the Record’ by the lesbian art collective fierce pussy. The collective, though founded in the early 1990s, came out with this piece in 2013. It is a lively grief for those who dwell in the lover’s eye, a grief that comes from losing anybody and knowing anybody could have been the beloved.

Due to the fact that AIDs is held in the body, everything was doubled: here is the unique face, here is the death. Save the face, spare it from the death.

Knowledge of climate change came into this world from the top down. It was caught on to by scientists in the late 80’s who exposed the idea to the government and the parasitic corporations that stay close to it. From there, the science was debated and oil companies got a head start on influencing public opinion. Putting aside the expected bullshit of oil companies, there was another result. The language and visual life of climate change was dictated by scientific mode and bureaucratic standards, rendering it merely data for most people. Without any personal experience of harm or difference to confirm the concept as real, it remained unreal. It stayed nebulous, attacking everyone yet no one at all.

Climate change must be shown to be as personally impacting as it truly is. We must find what we are losing and what is at risk. I already fear for the climate refugee who will be forced to cross an already killer desert. Avoiding, with any luck, border guards of the nation who displaced them in the first place. We should all cry our specific cries. I read about climate change, and it is just a tidal wave. Let it be a face I want to protect.

Ghibli but not cottagecore.

I credit Miyazaki’s movies for the values I have today, even if I don’t always act on those values. The tales these movies tell reframe the quest narrative. These are typically individualist, ‘heroic’ in the sense of cutting through obstacles, craving escape from the bonds and burdens of community. In the following links, you can find an expression of this idea by thinkers much better than I, with detail to back up the claim: Rebecca Solnit, Ursula Le Guin, and Anna Tsing. They all draw from Virginia Woolf’s definition of heroism as botulism, a fatal illness caused by some neurotoxic bacteria which cannot be tasted, smelled or seen.

The typical hero drives the narrative to take this particular shape –as described by Le Guin in the afore linked piece The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction– “first, that the proper shape of the narrative is that of the arrow or spear, starting hereand going straight there and THOK! hitting its mark (which drops dead); second, that the central concern of narrative, including the novel, is conflict; and third, that the story isn’t any good if he isn’t in it.” This conflict, though feigning a concern for the “light” that exists in the dark villain, doesn’t go beyond a binary consideration of who is on the inside and the outside of the group, who are the good people who should live. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a Miyazaki film concluded on the celebratory climax of the killed villain.

Instead, the Ghibli films led by Miyazaki prioritize a love of home and the people who live within it. The joy found in the Ghibli film is often a domestic one. The careful spinning of daily life that is not bound to the home. Adventure is not predicated on the abandonment of community, but precisely in the quest to keep it together and expand the net of care.

The girls at the head of most of these films are not the typical hero. They are not endowed with exceptional strength, magic, or intelligence (the heroes we worship IRL are these wunderkinds, and we wish to be them, and how do so many of them end up? Trust fund managers??). Sophie from Howl’s Moving Castle is an old woman. Mei of My Neighbor Totoro, and Sosuke of Ponyo, are just five year olds. Chirhiro of Spirited Away, is also a young, plain girl. Even Kiki of Kiki’s Delivery Service, the witch of the group, can only do the bare minimum–fly. They are surrounded by the powerful, interesting, storybook characters, and yet Miyazaki tells us that isn’t where the value lies by not utilizing them as protagonists. Instead, he says watch this child who is uniquely loving- lovingness which hasn’t been fossilized by fear of weakness.

This touches everything. When heroism is grounded in care of community, meaning EVERYONE and EVERYTHING, where does the urge to dominate find ground?

There is no place in that behavioral system for the kind of greed, power building, and sightless ambition that validates those who choose profit over people and Earth.

And I say not cottagecore because: How often are those pictures of cozy cabins, fields of flowers and cows populated by people? People, children and elderly working, playing, dying, cooking, doomscrolling–and asking you for things all the time. Needing you to be present and do things you don’t want to do. It’s like that feeling when you’re with your fucking family. Cottagecore is let me be away from people, let me be alone on domesticated land. So, no, not cottagecore.

Let’s make this a living document. Should you have any suggestions for this list, please email me at shanti.esc@gmail.com. Depending on the results of my gatekeeping, it shall be added here with credit.