A Conversation With Louis Osmosis

Louis Osmosis (b. 1996, Brooklyn, NY) is an artist working primarily in sculpture, drawing, and performance. For those unaware, Louis is a rising star in the New York art scene. He recently had his first solo show at Kapp Kapp, and is already preparing for his next solo at Amanita in the East Village. Louis and I became friends our Freshman year at The Cooper Union, and have remained close since. This interview provided an opportunity to reconnect, and chat about art, like all those years ago. We reference an essay by William Pope.L titled “Canary in the Coal Mine”. For those interested you can find the essay below, as well as a link to an essay Louis wrote recently published in the latest issue of the Brooklyn Rail. I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did.

Interview by Santiago Corredor-Vergara (aka memeadmin)

L: Anyways, did you read the Pope L. essay I sent you?

S: I did, there’s a lot to unpack…

L: Isn’t it great? I love…I would never say it’s a necessity, but it’s such a nice bonus when artists can write well, and write interestingly. I’ve fully bit his writing style. Bullet point format meets the un-poeticized stanza format, like, 2008 blog format too. The early aughts critical thinkers all had a BlogSpot, like that. That’s fully my vibe right now. The kid low-key has writing practice.

S: So what are you working on right now?

L: Well…other than Feng Shui-ing the studio with Oscar, getting it in order, I have another solo show coming up in March…

S: You’re unstoppable

L: I’m just in my bag, as my people say, I’m in my bag. It’s at this gallery called Amanita. It’s at the old CBGB, literally a couple blocks down from Cooper. So full circle moment. Yeah, I’m going completely nut-mode with it. That’s what’s on my platter right now.

S: Are you making new work for it?

L: Yeah, it’s all new work. I don’t want to give away too much. The element of surprise is as much a moment as it is a material. But I will say, what I did with my first solo at Kapp Kapp, I am not gonna be doing at this solo.

S: And what’s that?

L: I’m trying to do everything I can to retard sculpture, as in, like, stupify it.

S: As in making it slower or making it dumber?

L: You know, connecting with Canary in the Coal Mine, how the live-ness of the thing is contingent on its dead-edness? I’m trying to work out an inverse way of pointing to the efficacy of sculptures that are more object oriented. There are sculptures and then there are objects, and I think this show is gonna be way more sculpture-oriented than it is object-oriented.

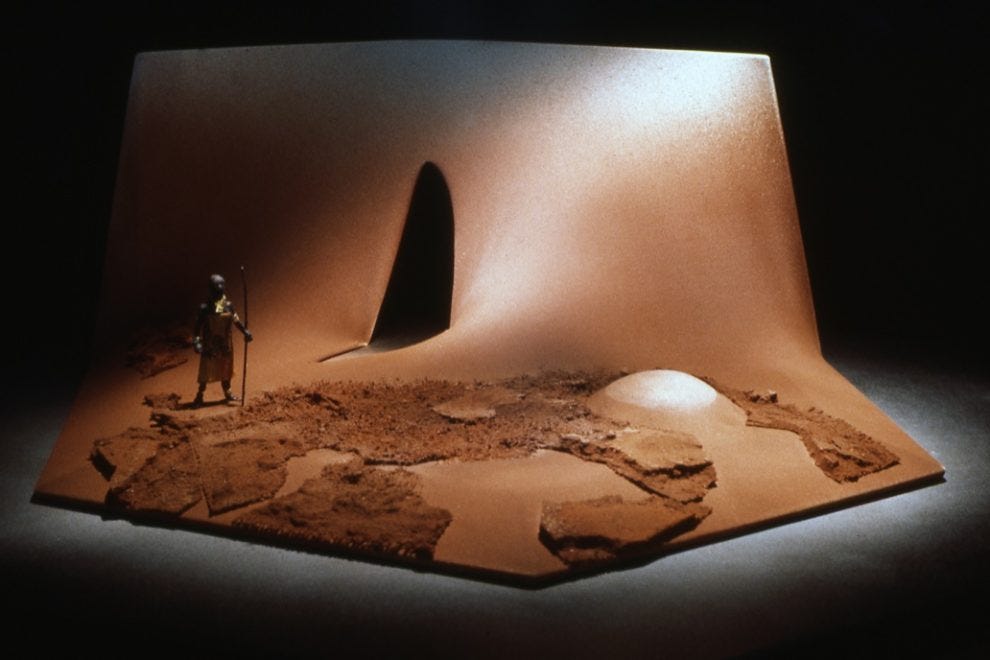

The solo I did at Kapp Kapp, I think was a lot more interested in an object-oriented economy, as this sort of like cultural gauging type of moment. But this show, I’m really going to lean into the theatrics of it. I’ve been looking into stage design recently. I went to a random bookstore, they had a section on just stage design. It just hit me.

I’ve also really been into monoliths recently, which is such a fuckboi thing, more for their market viability in terms of sculpture, but also for practicality. A monolith is as close as a sculpture is ever gonna get to a painting, in terms of real estate. There is this immediate dead-edness to the monolith, it’s just a nothing form, which is really beautiful. See all of post-minimalism. So yeah…

Something I’m trying to still work out in my noggin…that type of culinary arts where there’s this obsession with this analytic deconstruction of food. Like a salad broken down to its bare components. One leaf, a drizzle of dressing, and radish served on a huge-ass plate.

S: The culmination of that is molecular gastronomy.

L: I relate it as a sort of distant cousin of what I would call scatter art.

A strategy that evolved out of Kunst. Think of Lutz Bacher. A bunch of stress balls scattered across the floor. Or like, Danh Võ, making the statue of liberty to scale, but presenting its parts, intermittently installed in a giant place. That methodology of work is sort of one and the same with what I was talking about, this molecular gastronomy, and culinary presentation. I like relating the two, because I think the culinary moment of deconstruction of food items is a lot more flagrant with its market position. It’s like wealth crime, this is like the food of wealth crime. Which is cool, which is great. No moralizing.

S: It is what it is.

L: I’ve been thinking about those two things in tandem with one another, so far when relating this flagrancy, that reveals itself, that I really like. We love fragrancy. It’s one of my favorite words.

S: Can you unpack that?

L: It’s like that old adage. I prefer my racism to be overt rather than codified. When things are flagrant, the square-one moment you are confronted with forces you to reconcile where you stand in relation to it. You have to deal with it. It trims the fat. There’s no need for a back and forth, of figuring it out, interrogating it. That’s out.

S: So the flagrancy circumvents the need for debate, for discussion, it’s out in the open, plain for everyone to see…something like that.

L: Yeah. So, this get’s back to why I love a good pun. To the same effect that flagrancy trims the fat, and has you land in the middle of the action, you know, there’s an immediacy to that; an “oh” moment, an “oh shit” moment. Or, when there isn’t, that’s also cool, because it creates a split audience. Those who are in on the joke and those who aren’t. That creates its own mini forum. The works proliferate in different ways via the split audience.

S: Let me summarize quickly, so I can wrap my head around all of this. So we began with molecular gastronomy…

L: The Michelin mentality (laughs)

S: Right, this type of food-making deconstructs a dish into its bare components. In terms of strategy or methodology, you relate this to Scatter Art, which itself deconstructs the piece into its bare molecular components. When comparing the two, a flagrancy (the wealth crime) inherent to the culinary deconstruction is revealed. You’re interested in this directness as a mode of making, right?

L: There’s a straight faced-ness to it. There’s also this idea that all good artists are good because… they’re rarely ever good because of this listicle format review of their work. That makes clear what makes a good artist is their sensibility, that’s their driving force.

S: I think that’s not really plainly obvious nowadays…I could be wrong…

L: No, I agree, I think that’s really true. There’s a new cultural recoil every day, so much so that it starts to feel like a resuscitation of culture, but when something is constantly being re-animated that it only points to its dead-edness. It’s dead on arrival, that’s all I see, when something is being reanimated so violently.

S:In fact, you could say Western civilization itself is living only thanks to life support.

L: Right, and to your point, about “it” not being that obvious, I think that’s why, with a lot of the work I see, nowadays, especially with this type of stuff that’s really involved with this anthropological take on some niche aesthetic, like lowercase “a” aesthetic, it kind of indicates to me that, there’s this fetishization for topicality, subject matter, instead of what the works can actually do. The question of “how” is infinitely more interesting than the question of “what”.

S: Would you say that has to do with a kind of reterritorialization of art-making, a forced return to representation? Maybe in terms of market desires?

L: Again, to circle back, to bring up another “re” word. The prefix “re” to your point about representation, every time I hear “representation” I hear “resuscitation”, the painted figure is nothing more than a cadaver, a corpse. I have mannequins a la Isa Genzken. I mean, I only bring up the mannequins, because Isa Genzken’s use of the mannequins is a great way to counter the representation paradigm, insofar that only the idiot would encounter the mannequin in the context of art, and try to relate it to the body. It has nothing to do with the body.

A mannequin is first and foremost a display object, a mode of display. I think of her mannequins as a marker of the stupification of the figure by making it into an actor. These are dumb actors. Dope-ified. You have a mannequin wearing a football helmet, or holding a spatula and wearing a cape, or going through a tower. Again, there’s flagrancy to the nothingness of the gesture, of using a mannequin that I really admire, there’s a quickness to it. With that comes this sort of justification of the ease of the gesture, how do you justify this nothing moment. That’s what I’m saying with the square one thing, you arrive at it, and you’re flummoxed. You’re just like “oh, ok word, this is is some bullshit”. We love it.

S: Right cause you’re encountering a flat shape, with nothing behind it.

L:Well, you’re encountering a display aka art, which is just made of a display object, aka, a mannequin.

S:Right, it’s an ultimate tautology, A=A

L: I’ve been on a journey to try and get more mannequins so I can get a nuclear family. It’s very Charles Ray. We love his chrome silver mannequins. I got to get these for free. I refuse to pay for one of these. I’m still looking for a Mommy mannequin, the super ubiquitous ones. No hair, no facial features, just silhouettes, I’m still looking for a Mommy and a Daughter, I already have a Daddy and a Son. (Louis actively looking for the missing mannequins, if you have any leads, please contact him).

So, my mental prompt for this, on some Cooper vibes, because every piece I make, I start with a prompt for myself, the prompt for the mannequins is “how can I zombify a mannequin, how can mannequin-ify the mannequin, without it reading too poetically?”. We love poetics, but we’re not too big on poetry. This is the type of prompt that I would categorize in the larger umbrella of my thinking, as being in the realm of redundancy. I love redundancy as a strategy.

S: To mannequin-ify the mannequin, is that an additive or a subtractive process?

L: I don’t know. Not to get too nerdy with it, but I think of it more like it’s kind of like embedding a concavity within the thing. It’s like putting a hole in its spirit, in like, the soul of the work, or rather excavating the hole in the work, the flaw, the scar. Redundancy is a great strategy because it sets up the terms of the work as only the work, the terms are just the work, and what it is. Its self contained, enclosed, ecosystem. And this is not autonomy. It’s a way of starving the work of content, of any external material. Starving the work with the objective of “freeing” it.

I’m gonna write this down for myself, but if there was a name for this tactic, it would be “twist and shout” (we both sing the line and laugh)

S: At the end of the day you’re an easy guy to interview. You got stuff gnawing away at your brain. I also think great artists “think” in art. I feel like my mind is too plagued by philosophy and politics. A hell I can’t escape.

L: I mean, I don’t know, not to speak in broad strokes, I hate using this word, cause it’s such a sculpture-bait word, it’s like imperative to maintain a lateral thinking. It’s the reason why I said that I was gonna do everything in my power to not do what I did for the Kapp Kapp show this time around at Amanita. It’s honestly out of fear, I don’t want to bore myself. I am my own worst enemy. I hate myself . Like “My guts, yuck”.

In a twisted way, I think, a show is a good way to set yourself up for disappointment. No matter what, people always feel like post-show blues. Let me look forward to this moment of disappointment. There’s something really beautiful to be able to arrive at a deep-seated sunken-ness, and have that be a generative moment, with the edge being pessimism here. There’s something really enthralling about that.

S: There’s a certain freedom to pessimism, for sure.

L: You know, laughter is the greatest medicine. We’re collectively sick. We’re collectively diseased. That’s where the crude, humorous moments can hit. It’s like a dissonant piano moment. You know when someone plays Für Elise and they fuck up one note. Like “what the fuck did you just do? Did you just piss on my leg?”

S: Would you say your work is a punchline for the end of the world?

L: Nah, that’s too doomer-y. The onset of things is all but a forecast of their death. The onset of things only names its “dead on arrival-ness”. This is not to be misconstrued with nihilist defeatism. It’s more of an opportunity to embrace that. In a Fisher way, there is to some extent, no, to a great extent, something very life-affirming about the contemporary culture at large that we live in now, considering that it’s only caught up in this cannibalistic revivalism.

Long story short, in the sense that there’s nothing new being produced, and nothing new is being maintained. That in it of itself is a new thing. Everything has been spent and run dry. That’s the first time that that’s happened in culture, and there is a collective recognition to be had. I really feel that in the pits of my body. It’s a beautiful thing. It washes away a lot of these cobweb laden responsibilities that have been flung at artists for the longest time. I’m just a Joe Schmo A jabroni. I’m a dub.

S: It’s the ultimate challenge of true freedom.

L: To that, I actually have had this mental image in my head for a minute, I don’t know if it would be a good piece, per se. But I’ve always wanted to have my little cousin Matthew or Fay or Fay, to pose next to a science fair board, those three-folded cardboard things, and have it say nothing except for in the middle: “how to die happy”. Have them pose like grinning ear to ear. I dunno, that makes me think of that. It resonates.

Here the conversation trails off for a moment and we get side-tracked.

L: Let’s circle back real quick, to the point about theatrics. There was this mantra that was championed in regards to sculpture, you know, “the minute Sculpture becomes a prop, it becomes a bad sculpture”. That kind of just sat in my brain for mad long. I bring this up in relation to theater and theatrics, in the case of the stage-prop, as a form to work with. I do agree with that sentiment, but I also think there is something really potent in the dumbness of that type of position for an object, and trying to have sculpture do that. Align itself with that same dead-edness, and that same type of presentation, but have it work in a different trajectory.

That’s why I’ve been having a Samuel Beckett moment. His work is so annoying to read, and I’m a slow reader as it is, but especially so with Beckett. It’s like a slow burn take on something that isn’t affirmative, it fucking sucks, but I love it for that. A slow burn that isn’t affirmative. The book I just finished, which I’ve read three times at this point, How It Is, is a crazy set-up. It’s essentially a play in three acts, and you have a protagonist, and he’s the only character except for this other character named Pim, and the whole play is about the main character trudging through mad. That’s literally it. There’s no syntax. No care for grammar. Rarely anything is capitalized except for the other character, Pim. There’s this disparate-ness that I really enjoy.

The closest I’ve gotten to it, is this “nothing is precious” type of mentality, nothing is sacred. It’s all equalized, leveled out. That’s been a huge thing for me to chew on for this next show, and for this next body of work. Also to the stage design point, this dude named Ralph Koltai, insane. I’m less interested in this surrealist bend that his work might have, I’m more interested in how these things are installed. This almost Mad Max-ian level of abstraction that he does with a lot of the scenery.

S: The word that comes to my head is “totalitarian”. Like a “total” work of art, in the Wagnerian sense. The artist has, following Groys, has total dictatorial freedom to impose their vision…

L: I have a very different way of thinking in regards to that. I wouldn’t call it totalitarian, I’ve always maintained that an artist in a gallery is the equivalent to a guest in a house. The way I see it is, how do you enter someone else’s house, and knock it down a peg, without making it so obviously about “vigilante poetics”. Because then you become, no pun intended, “arrested”, by the optics of your work, how it’s perceived. I wrote a little poetic essay, it’s a short little thing for the next Brooklyn Rail. Essentially I wrote about espionage and perversion. The question is how do you make it so that that ambivalence reads tactilely. A gallery is a great place to level things, because it’s so heinous. We have to part from the fact that everything in hell is hell-ish.

S: Reading the Pope L essay, there’s this notion that the poverty of objects signals something lost, an absence. It makes me think that being mad at Duchamp for allowing for anything to be an artwork is misdirected, because actually it’s a much larger issue. It’s really a generalized loss of metaphysics due to a total commodification of all things under capitalist social relations. The desert of the real.

L: For sure. But, you know, absence is the most fertile land in the contemporary landscape. The most fertile place is the desert, the tundra. To the Duchamp point, when you talk about commodity and Duchamp in the same sentence, this is why Jeff Koons matters. He hyper-commodified the ready-made. Not only did he do that, he also revealed the capacity to be a commodity.

S: It’s an obvious gesture though, in the sense that we already know that everything is or can be a commodity. We don’t need Jeff Koons for that.

L: Sure, but there is a difference between a simple commodity and wealth-object. A commodity doesn’t necessarily come with Spectacle. A wealth-object introduces itself first and foremost as Spectacular. Via hyper-craft and hyper-production, he can reveal the “innards”, the wealth-object that was always latent in the ready-made.

S: I feel like there was a utopian gesture in the Duchampian ready-made that’s completely eviscerated by Koons. What I mean to say is that the Duchampian gesture was quite democratic in nature, because it signaled that anyone could be an artist, which is the opposite of the Koonsian gesture, which obviously requires an ownership of a certain “means of production”.

L: But like democracy shmecmocracy, you know. It’s blunt. It’s so obvious. It essentially pulls the wool back, and pulls it back over your eyes. It reveals a latent economy that had just been lying dormant, sleeper agent shit.

S: That’s capital. Capital is always sleeping dormant in all codes and forms. He just had to untap it. Untap the flow.

L: That’s a beautiful gesture. Doing it in art is different from doing it in real-life. Art and the artworld and the art-market, are like a petri-dish for life to reveal its innards, its guts. It’s cool because there’s this visceral hyper categorization especially in terms of class, with this monetization of the ready-made. Imagine dying and going to Heaven, and there’s a cover-charge to get in. It’s like “ladies free all night, fellas ten dollars at the door till midnight”.

S: That’s exactly what I’m talking about, the commodification of the last possible thing that could ever be.

L: Yeah, the supposed last frontier. That’s cool because the gambit is revealed. The last frontier was never an asset to begin with. If the thing is what it is now, it has always been that from the beginning.

S: It’s interesting we arrived here, because the entire point of the essay you sent me was using performance art as an example of something that’s perceived to be immune to commodification, but that in the end is commodified. These are interesting concerns.

L: To that point, in regards to that final frontier, performance was historically conceived of as this final frontier, this supposed non commodifiable thing, you know, ephemeral, not even concerned with time, but contingent on time. There’s this unspoken fetishization of performance as a medium within the last five to ten years. Follow the paper trail, follow the money, the language used by these grants and institutions, when patronizing performance work. It’s always about the identity of the performer, even for the performance art in which the artist is a choreographer and not necessarily participating in the work. They’re still lampooned as the face of the work.

This is part and parcel of this fact that in contemporary art, where instead of like how it was back in the day, in which the work gets you to the artist, now it’s the other way around, the artist is the first threshold to understand the work. Essentially, the perceived character of the artist, but also the self-narration that the artist involves themselves in, precedes the work itself. This goes back to the essay, thinking about documenting work via rumor or gossip, rather than photo documentation.

This also has to do with this digital space at large. An example would be Lutz Bacher, while she was on this earth, she didn’t let anyone take a photo of her, using a fake name. Or, David Hammons, when he pissed on the Richard Serra, and the photo documentation of it also had a picture of a cop supposedly arresting him. It was never confirmed whether that was plant or not. The artist as a rumor of themselves. The artist as their own press. That’s something to work with.

S: Does the medium become reality itself?

L: I wouldn’t put in such broad-stroke philosophy terms. I would say the medium is “optics”. Yeah we could say optics and perception revolve around “reality”, but let’s just call it what it is. This is also buttressed by the fact that the market precedes artmaking. To circle back to what we discussed at the jump, this hell-bent obsession that a lot of artists have nowadays, especially downtown painters, have for topicality, and subject matter as this means to an end, which rarely ever works.

S: Can you give me a concrete example of that?

L: OK, I’ll use the downtown painter example. So many of these dudes are painting goblins, and demon-core stuff, and then guess what, they say that the work is literally about demos and goblins. (laugh) You paint fantasy, and you ask them about it, and they say it’s about fantasy.

S: That’s why I said at the beginning this concern for representation.

L: I obviously think about figuration all the time, but that’s why I don’t use any of those–when I think of figuration I use a mannequin, a dummy, a puppet. Things that are modes of display that are contingent on a mirroring of the viewer first and foremost.

S: I feel like, “painting is dead, long live painting”, fuck it. Painting has its virtues goddammit. I guess painting’s virtues lie in the painter’s sensibilities though.

L: It’s pretty much only that. I like provisional painting. Like Michael Krebber. The daddy-o of provisional painting. White canvas, one blue line basically.

S: I’m thinking of this guy, Majerus?

L: Oh yeah, he’s fully having a resurgence right now, as he should. His paintings are very prescient.

S: Yeah, his paintings aren’t caught up in naïve longings.

L: I enjoy provisional paintings for their market viability. It’s the type of stuff my father would look at and be like “what?”. It’s cool because beyond the market viability which is an in-the-know artworld type of concern. There’s also the Joe Schmo concern that I was talking about earlier, which is the aesthetic justification of thing, and we love it for that.

But yeah, in March look out for the next Osmosis drop. It’s really like that meme of the psychopath inmate with the psychologist, and the psychologist is like “so are these ‘big things coming’ in the room with us right now?”.

We both laugh, and the interview gracefully comes to an end. You can follow Louis on Instagram @louisosmosis .

You can follow Santiago on Instagram @pl0xi_the_arsonist.

https://brooklynrail.org/2022/09/criticspage/Club-of-Joe-Schmo – link to the essay written by Louis

Canary in the Coal Mine – William Pope.L, 2011